Over the weekend, I crossed another dream off of my bucket list. The Illinois Railway Museum hosted its annual Diesel Days, a celebration of diesel power in railroading. Each year, the museum offers a rare opportunity to become an engineer for a short amount of time and control the power, braking, and horn of a locomotive. I got to take control of a wonderful piece of history: A 1954 Alco RSD-5 painted in a Chicago & North Western livery. This locomotive, with its 1,600 HP V12 prime mover and six axles, is just one of two operational survivors. This is what’s like driving an old locomotive.

This year, I’m having another summer of dreams. I’ve been able to visit incredible places that I never thought I’d ever see, I got to drive a variety of lovely machines, and plant my stakes down at events I’ll never forget. The Lockheed Constellation from EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2023 is burned into my brain like a CD-R from the 2000s [Ed note: Best of Trip Hop Volumes 1-3 – MH] and the memories of the Ford F-150 FP700 still make me giggle. Still, the summer isn’t over yet and thanks to the Illinois Railway Museum, I got to see another dream fulfilled when I took control of a diesel-electric locomotive.

A Mission To Drive Everything

Taking command of a locomotive has been a lifelong dream. I’ve adored trains for about as long as I’ve admired planes. As a kid, I had dreams of gracefully flying through the skies in a Boeing 747 or a Bombardier CRJ-700 while at the same time dreaming of holding the throttle handle of a Chicago Metra EMD F40PH locomotive. This only intensified when I first saw the majestic EMD F40C locomotives in Metra’s fleet. My love for aircraft and trains has persisted for about as long as I’ve been fond of cars and buses.

As an adult, my attraction to various forms of transportation has evolved into what I think is one of my life’s missions. I want to drive, ride, fly, sail, and operate as many vehicles as I can get my hands on. If the vehicle has wheels, tracks, wings, or a hull, I want to see what it’s like to take command of it.

Do you remember Discovery Channel’s Dirty Jobs? In that show, Mike Rowe would go out in the field and perform some sort of dirty, difficult, weird, or just outright disgusting jobs. In the end, each episode usually highlighted the work a lot of people do that most people never know about.

Of course, I have no desire to find the vehicle equivalent of a sheep castrator, but I want to experience the vehicles that most people may never touch, let alone operate. What’s it like being at the helm of a cargo ship? How fun are those gigantic mining trucks? What’s it like flying those expensive eVTOLs all over the news? Can a Smart Fortwo tow a plane? Those are questions I’d love to answer and more.

Many people have seen trains and have ridden in passenger cars. Railfans will get into a long line just to take a picture of a train. Fewer will ever get the chance to enter the cab of one of the locomotives pulling or pushing those cars. Until Sunday, I was one of those people. Sure, I have been lucky enough to go into a locomotive’s cab, but I couldn’t tell you how a loco drives, until now.

Diesel Days

My train drive took place at America’s largest train museum, the Illinois Railway Museum in Union, Illinois. I’ve written about IRM a number of times in the past, but for a quick reminder, the museum was founded 70 years ago as an effort to preserve local railroad history. It has since grown into an impressive display of over a century of railroading. IRM’s collection includes about 500 pieces of rail equipment, about five miles of right-of-way, and around four miles of track on its impressive 100-acre property.

One of the greatest parts about IRM is that so much of its equipment is operational history. An IRM volunteer told me that the museum has over 50 operational diesel locomotives. That’s in addition to its countless passenger and freight cars, buses, various steam locomotives, streetcars, speeders, interurbans, and more. The Illinois Railway Museum has the same kind of magic found at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh, but you can experience the greatness throughout most of the year. The museum’s calendar is also chock-full of special events that keep you coming back.

Diesel Days were exactly as it sounds on the tin: three days of rumbling, thunderous diesel-electric power. On Diesel Days, IRM’s electric and steam trains get a break as volunteers hop into the cabs of as many diesel locomotives as they could fit into a weekend. There were many locomotives operating during Diesel Days that you wouldn’t find running on any other weekend.

Diesel Days also offers two unique opportunities for just a handful of people. For an affordable additional fee, you can ride in the cabs of one or more of the locomotives running down the five-mile mainline during Diesel Days. You’ll get to watch the action happen as the engineer pilots a piece of history down the line and back to the depot.

If you’re looking for something a little more engaging, during Diesel Days, a handful of people will have the chance to “Take the Throttle” of a locomotive. The museum offers a Take the Throttle program that runs Saturday and Sunday evenings May through September. When you take the throttle of an IRM locomotive, you take full control of a diesel, steam, or electric locomotive while an IRM engineer teaches and supervises you. The main program lasts for an hour.

However, slots are limited and have to be reserved well in advance. That’s a bit difficult if you’re like me and may end up in, say, Detroit, at the drop of a hat. Thankfully, Diesel Days offered a condensed version of Take the Throttle where you get to drive a locomotive at a set time for about 20 to 25 minutes.

On top of that benefit, the Diesel Days version of Take the Throttle also has equipment that changed throughout the day and throughout the weekend, so you could drive different locomotives on the same day if you wanted to.

The American Locomotive Company

By the time Sheryl signed me up for Take the Throttle, most slots had already been taken up. Thankfully, she was able to score me a position at the controls of Chicago & North Western 1689, a 1954 Alco RSD-5. As it turned out, this piece of equipment is a real piece of history.

American Locomotive Company (ALCO) was formed in 1901 after Schenectady Locomotive Works merged with seven smaller locomotive manufacturers on the east coast. During Alco’s 68 years of existence, it built more than 75,000 locomotives, a number that includes more steam locomotives than any American manufacturer except for Baldwin Locomotive Works. Some of Alco’s products include Union Pacific’s Big Boy, the RS-1, and oh yeah, the company also got into nuclear reactors and Berliet cars.

As Railfan & Railroad Magazine writes, Alco was an early innovator in diesel-electric locomotives. Back in the 1930s, Alco was one of the pioneers in diesel-electric switchers. Those are the types of locomotives often found moving rail equipment around short distances. Railfan & Railroad Magazine goes as far as to say that Alco’s HH-600 was the first practical switcher with an end cab.

In 1941, Alco would make history again with its RS-1. So many of the locomotives today have a design that could be traced back to this unit. As the story goes, back in 1940, the Rock Island Railroad approached Alco with an idea. The railroad wanted a locomotive that could function as a switcher and be used for hauling freight down the road. In theory, the railroad could save money if it had locomotives that hauled freight by day and then shifted cars around by night. The result was the E-1640, or RS-1, which is often referred to by railfans as the RSD-1 when referring to six-motor models. These locomotives, as Railfan & Railroad Magazine writes, were the first road switchers.

What made the RS-1 and thus the road switcher so revolutionary was its narrow, slender hood. The typical diesel carbody of the day had little rearward visibility. Yet, thanks to the RS-1’s narrow hood and low-profile engine, a train crew could see both in front of and behind the locomotive. This allowed for far easier operation in either direction. American Rails notes that the raised cabs of Alco’s road switchers were the work of industrial designer Otto Kuhler.

Power in the RS-1s came from the 539T diesel, a turbocharged straight-six making 1,000 HP. That provided power for motors with 72,000 pounds of starting tractive effort and a rating of 34,000 pounds tractive effort at 8 mph.

The RS-1 was followed up with the RS-2, which featured a more rounded body and 1,500 HP to 1,600 HP thanks to a new V12 prime mover. That locomotive was developed into the RS-3, which featured more engine and design refinements, and the RSD-4, a development of the RS-3 featuring two three-axle trucks for a greater starting tractive effort.

Indeed, an Alco RS-3 put out 60,100 pounds of starting tractive effort and 53,000 pounds continuous while the RSD-4 achieved 89,000 pounds starting tractive effort and 78,750 pounds continuous tractive effort.

The Locomotive

That brings us to the locomotive you see here today. Built starting in 1952, the Alco RSD-5 is a development of the RSD-4. Reportedly, a problem with the RSD-4 was the fact that its body wasn’t long enough to support the locomotive’s main generator. Just 36 RSD-4s were built and Alco raced to fix the problem by introducing the RSD-5. The RSD-5 features a longer body to accommodate that GE GT566 main generator as well as minor improvements such as a 90,000-pound starting tractive effort and 100 more HP. American Rails that the RSD-5 was far more successful, selling 204 units in North America.

The prime mover is an Alco 244C V12 turbodiesel engine. Each cylinder displaces 10.9 liters for a total of 109.4 liters of displacement. It’s good for 1,600 HP and as I said before, a 90,000-pound starting tractive effort through its two trucks of three axles with six GE 752 traction motors.

Chicago & North Western 1689 is an RSD-5 that was built in 1954. IRM has not yet written about this unit’s history, but volunteers tell me the unit ran with Chicago & North Western until its retirement in the 1980s. The Illinois Railway Museum acquired the unit in 2014 and the museum has been using the locomotive on its demonstration railroad ever since.

I got to chat with one of the mechanics keeping 1689 running and I’ve learned that there are some parallels between keeping an old car alive and keeping a locomotive alive. The museum volunteer told me that batteries are a huge expense. As you could imagine, starting a 109-liter engine is no easy task. Many locomotives use their generators to start their diesel engines and the starting batteries themselves are pretty nutty if you’re only used to car or maybe semi-tractor batteries. The mechanic told me that locomotive batteries weigh hundreds of pounds and even a full complement of batteries for a small locomotive can weigh 800 pounds. Here’s one that weighs as much as a Smart Fortwo!

Once the mechanic cranked the mighty RSD-5 into life, I noticed that the prime mover never quite fell into a rhythm. I’m told that’s fine. It’s not really broken and there’s no need to do fine tuning just to smooth out the engine.

A quirk with Alcos that many railfans love is how much they smoke. This smoke is generally caused by turbo lag. For example, the IRM engineer had me crank the RSD-5 to notch 5, full throttle. The engine belched out smoke as if it were a steam locomotive, then the turbo finally caught up and the smoke cleared up a little. A few of the volunteers I talked to said Alcos smoked so much that they were basically honorary steamers. One of IRM’s Alcos has a seized turbo and thus it always has an incorrect air-to-fuel ratio, resulting in epic columns of smoke.

Driving A Locomotive

After I learned the history and the mechanics of the 56-foot, 287,000-pound machine, I climbed the stairs and hopped into the cab.

Now, while the RSD-5 can easily run in either direction, long hood forward is officially the front of the locomotive. When you sit in the cab, you’re presented with a plethora of switches, toggles, and an armada of levers to pull. It seems daunting at first, but take a deep breath, and if you’re a car person, a lot of bits will become familiar. Gauges inform you about your speed, the engine’s temperature, the unit’s battery voltage, air pressure, and more.

The various levers also look a bit intimidating but they’re pretty easy once you learn what each one is for.

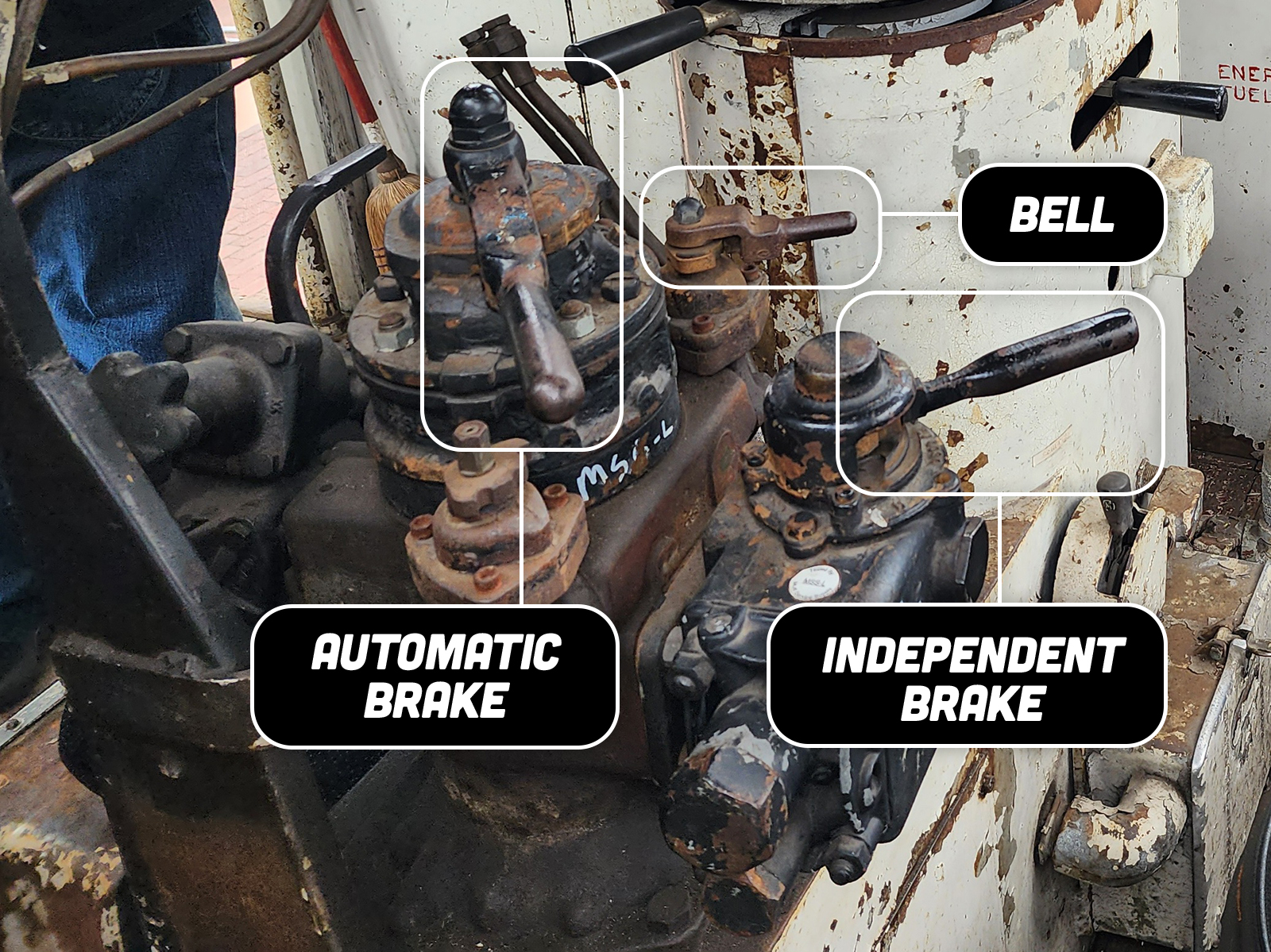

Just under the gauges of the white control stand in the middle is the throttle (top) and the reverser (bottom). The throttle is notched with numbers. To set your throttle, just move the lever into one of the notches. The reverser tells the locomotive’s drive system which direction to move (or not move). It’s pretty simple as you have just three choices, reverse, forward, or neutral. Toward the end of the control stand you’ll find brakes. This locomotive featured a lever (the one pointing toward your screen) for automatic air brakes, which weren’t needed since we weren’t hauling anything. Under that was the independent brake, which stopped the locomotive itself.

The tiny lever was for the bell and the string? That baby was the horn! And oh yeah, I got to yank that thing frequently. Can you say WOO WOO!!

Pulling out of the depot for my run, I was instructed to give that horn three short tugs. IRM uses two horn blows to tell people you’re going forward, three for reversing, and one after you’ve come to a complete stop.

Once I announced my departure, I released the independent brake, slammed the reverser back, and gave it one notch of power.

Fiction Vs. Reality

Now, as I said before, I’ve loved trains for pretty much all of my life. Growing up and even now as an adult, I’ve always had train simulators and flight simulators on my computers. I repeat real life flight lessons in X-Plane as a way to practice what I’ve learned. I had hundreds, if not thousands of flying hours in Microsoft Flight Simulator X before I even stepped into a Cessna 172’s cockpit. My flight instructor believes those sims are part of why my real life skills develop rather quickly.

Weirdly, my years of train simulator experience didn’t really translate well to real life. Sure, because of train simulators, I knew where the controls were and what they did, but the experience of driving the locomotive was nothing like a sim. Something I never really got from a train sim, even a really detailed one, is a sense of weight and speed. A Boeing 747 in X-Plane “feels” heavy, but a mile-long consist in a train sim gave me nothing.

In real life, with a V12 beating behind my head and nearly 300,000 pounds controlled my fingers? That sense of speed and weight I’ve been missing for so many years was finally there. The RSD-5 handled like it was on rails, because it literally was, but like a good communicative car, I felt like I knew what the axles were doing around my feet. If the rails were imperfect, the wheels were the first to let me know. As 1689 rounded the bend just outside of the depot, I moved the throttle into notch 2. The V12’s rumble grew, just barely, and I received a small dose of power, more than enough to climb the ever so slight grade. Two notches in and the engine was barely awake. This was a Sunday drive for the 69-year-old machine.

A few minutes in, I approached a grade crossing. IRM isn’t just a museum but a real working railroad. That means engineers have to follow the Federal Railroad Administration’s train horn rule. That’s two long blasts, one short toot, and one more long blast as you cross the road. I got to do that twice and wave at the traffic waiting for my crossing. As I worked my way down the west end of IRM’s mainline, the engineer taught me the basics of lighted signals. Green means I’m clear, yellow means I proceed with caution, and under no circumstance should I blow a red signal. On signals with switches, two green lights means I’m probably about to take the train multi-track drifting and I probably shouldn’t do that.

On Sunday, the Take the Throttle mainline route was set to go without any interruptions, so I had a red signal for the track I wasn’t concerned about and a yellow signal for the track back to the depot. Before I went back for the depot, the engineer let me get a feel of the brakes. First, I put the throttle lever to neutral, coasted for a bit, then began working on the independent brake. I learned that the independent brake had rather granular control, even more than a car or motorcycle. My target was a box just short of the end of the line and using the independent brake, I was able to nail my target right on the mark, coming to a stop with the sort of gentle halt you get during a nice commuter rail ride.

Next, I flipped the reverser forward and yanked the throttle into notch 5. This locomotive may have had just a 1,600 HP V12 under the long hood, but it was like I had opened the gates of hell just in front of my hand. Black smoke belched out of the engine’s exhaust as that V12 billowed out a mechanical roar.

Sheryl took a video of this! She told me she was a bit too distracted by staring at me so she failed to turn the camera down the line.

Acceleration was gradual, but I rode on more power and more torque than any car or truck I had ever driven. This Alco hauled like a freight train with the presence to match. Sure, an Acura NSX will go 60 mph in three seconds, but the train has the thunder and the power to move the ground underneath it. Heck, you can lose the entirety of the Acura’s displacement in just one of this loco’s massive cylinders.

As I approached the depot, I backed 1689 off of notch 5 down to a more reasonable notch 1. I blew my horn four more times at the grade crossing, rounded the bend, and stopped right on my target at the depot’s stand. As a final demonstration of the Alco’s power, I parked the locomotive, put it in Neutral, then let the engine run to full power. It was a triumphant finishing move of brutal horsepower and enough smoke to embarrass smaller steam engines. Roughly 25 minutes after it started, my ride was over.

A Dream Come True

My time with the RSD-5 was short, but I’m never going to forget it. IRM has informed me that this locomotive is just one of two of its kind left in the world. All of the others have been scrapped, left to rot, or have been rebuilt into other locomotives. IRM’s RSD-5 is rarer than most of our Holy Grail picks.

It was a blast taking the throttle of a living piece of history. Looking back, the locomotive was easier to get moving than a car and isn’t as complex as a plane, but there’s still a lot going on. Remember, you’re moving literal tons of weight and that mass doesn’t want to stop quickly. Stopping isn’t fast like a car, but gradual, just like the acceleration is. But don’t worry, the locomotive won’t let you forget that you have well over a thousand horsepower at your fingertips. And that’s not even close to some of the most powerful locomotives out there.

This experience has only motivated me to get even more train seat time, even if I’m just along for the ride in the cab. I’d love to see and feel how trains work in actual working conditions and see the world through one of the coolest offices in the world.

If you want to see America’s largest train museum, head down to Union, Illinois. There’s still plenty of time left in the year to take in more train history than your brain can process. And who knows, maybe you’ll catch me out there, living out my childhood dreams.

That’s so cool, you’re a total badass!

The look of pure joy on your face. I get it.

What wonderful writing, Mercedes! You really conveyed the joy well!!

Outstanding article!!! There’s nothing like those big diesel engines; I got to stand next to a running one earlier today for only the second time in my career. You can really feel them.

Another great article Mercedes! That would be so awesome to do…glad you had a great time

Living life vicariously through you Mercedes. I am not quite a rabid railfan, but I have a healthy interest and will take a ride on historic railroads every chance I get. Steam is my favorite, but I also like early diesel, when they had a little style to go with the function. Any DL109s there?

Finally got to read this article and loved it. Trains are fantastic beasts, and the engines that power them even more so. Used to go to oil fields and industrial plants with my diesel engineer dad, and those massive engines were just amazing. Had blocks in our backyard (granted, a really big yard), that I could have climbed into the cylinders as a little kid. Still gets me to feel the power of them just standing nearby, so I’m jealous you getting to run a locomotive!

Thats awesome! Congrats for living the dream, sounds like it was a blast!

I’m so happy you got to live your dream, Mercedes! Also, 69. Nice.

Rolling coal in your brodozer = Lame

Rolling coal in your locomotive = Badass

Thanks, Mercedes! I really look forward to your articles. Can’t wait for your next AirVenture installment.

This is fantastic! WOO WOO

But where are your Dickies striped overalls??

Very cool that you have a job that lets you live out dreams and pursue passions like this. This was a fun read.

Really cool. Thank you for sharing!

I am so jealous of you but also happy for you at the same time. That is so cool. I will HAVE to go to IRM one day.

This is an amazing writeup. The video was great too — I found myself rewinding and squinting my ears trying to hear what the background voices were telling you to do.

Union doesn’t seem too incredibly far from me. Might be worth a trip from downstate.

Great write up and photos! I went to IRM in the 80’s, looks even better now,