NASCAR has always seemed to be looked down upon for its old-school foundations. The technology may not be “new” per se, but the research and development poured into it would rival most other racing series. The Cup series has moved on to the modernized “Next Gen” platform leaving the Xfinity series cars as the last great American Stock Car. Come with me on a journey over these next couple of posts to explore what makes these racecars so special and how teams can optimize them.

Three-time Australian Supercars Champion turned NASCAR star Shane Van Gisbergen had the following to say when comparing the Xfinity series platform to that of the Cup series Next Gen with its independent rear suspension:

“I like the Cup car because it feels like every other car in the world I’ve driven, and then I got in the Xfinity car and had no idea what was happening. It drives like a forklift, the way the rear end moves, how it drives but if you speak to drivers here, they like it better. The rear end is really, really interesting, how it moves around. I’ve never driven a car like that.”

-SVG speaking to Matt Weaver in Talladega, October 2024

Understanding The Magic Of Truck Arms

For decades, the NASCAR rear suspension platform was on a desert island compared to literally any other racing series in the world. It consists of two truck (trailing) arms, a solid rear-end housing, and a track (panhard) bar. This truck arm rear suspension system serves two purposes. One, and most obviously, is to support the chassis and help balance the race car mechanically. The second is to create as much yaw, or skew, in the chassis as possible.

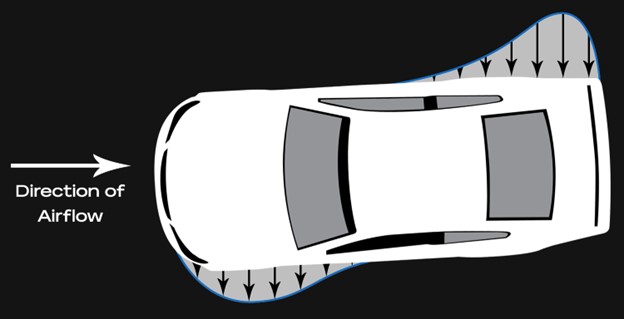

The more skew angle that a team can induce into their car, the more aerodynamic side force will be generated. Take a look at the Joe Gibbs Racing #54 Supra driven by Ty Gibbs in practice at Charlotte Motor Speedway below.

There are a couple of things to note from this image. First, you can easily see the amount of skew in their setup by looking at the distance from the white line to the left front tire versus the left rear tire. The car is not oversteering, you can see that his right hand is still at about 12 o’clock on the steering wheel, but it is literally hanging the back end out. The second thing you should notice is that the right side of the car is visible in this head-on shot. By offsetting the rear end, the right side of the car is exposed to the air. With mid-corner speeds often in excess of 160 mph (260 kmh), exposing that much surface area to the wind creates a substantial amount of force. The net force of pressure exerts a force on the right rear of the car and acts like an invisible hand pushing the car into the corner and preventing it from spinning out of control.

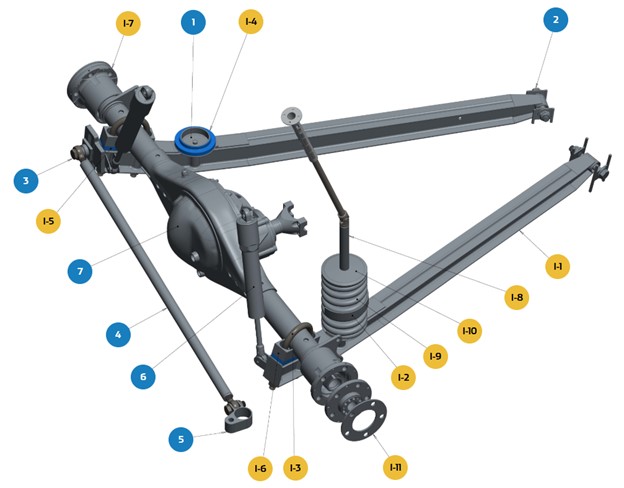

This aerodynamic side force can generate several hundred pounds of lateral force, almost like putting stronger magnets in the back of your slot car and trying to hold the trigger wide open. The force is magnified, up to a point, with increasing yaw angle. So how do teams use their rear suspensions to generate this force? A generic rear suspension setup can be seen in the below diagram from the NASCAR rule book.

The track bar, labeled with a blue #4 in the drawing above, supports the rear suspension laterally. The left side of the track bar is connected to the left side trailing arm at the blue #3, and the right side of the track bar is connected to the chassis at the blue #5. The left side mount height is a fixed part of the setup and the right side can be adjusted up or down on pit stops via a jackscrew in the rear window.

On track, the left side height is fixed dynamically, as it is attached to the truck arm, and only moves vertically with tire squish under load whereas the right side moves up and down with the chassis in travel. The center height of the track bar is the height of the rear roll center. For example, if the left side is at 6” and the right side is at 8” then the rear roll center is 7” high.

The dynamic height of the track bar has a dramatic effect on the handling of the racecar. On an oval car turning to the left, the track bar acts as a tension link between the suspension and tires, which are connected to the ground, and the chassis, which is being pulled to the right by the lateral force. Two cars can have the same roll center but drastically different handling characteristics based on the angle of the track bar. If the track bar is raked, meaning the right side is higher than the left side, the lateral force will be pulling the left rear tire up and effectively taking load off of it. With the track bar de-raked, left side higher than right side, the lateral force will be pulling the left rear tire down and into the track.

It is worth noting that the rear end will generate maximum skew with the track bar level. Raising or lowering the right side shortens the effective length and pulls the rear-end housing to the right. This causes the left rear to be less toed in and the right rear to be less toed out. For this reason, cars go through pre and post-race inspection with the track bar level.

Spending Millions On Track Bar Mounts

The left side track bar mount is an area of intense research and development for teams. Any amount of flex in this mounting assembly will allow the chassis to move further to the right relative to the tires. This creates a significant amount of the skew. A car’s rear steer angle will be checked in post-race inspection and if the system takes on too much permanent deflection the racecar will not pass inspection and the team will be disqualified. Untold millions of dollars have collectively been spent over the years researching the perfect combinations of materials and dimensions to stretch just the right amount and then spring back repeatedly and predictably without failure. Currently in the Xfinity series teams are allowed 0.29 degrees of static toe, roughly 5/32”, in pre-race inspection and 0.59 degrees, or 5/16” in post-race inspection. On an oval track car, the left rear will be toed in and the right rear will be toed out to cause additional rear steer.

Why Drivers Think They’re Spinning Out When They’re Actually Not

Temporary deflection beyond this point happens when the system has some give in it under lateral load, which can be quite uncomfortable for drivers. The car will have a transition moment on corner entry as it goes from its static position to its dynamic position. During the transition, the chassis will be rotating relative to the tires. Everything in a driver’s brain will tell them that the car is oversteering into a spin, but in reality, the tires are still stuck to the track and it is just the chassis pivoting. Let’s take a look at the system to try and understand how teams will try and get it to deflect. Keep in mind that the lateral force applied to this assembly can vary by hundreds of pounds from one track to another, so the design of the system that a team selects for each week can vary significantly.

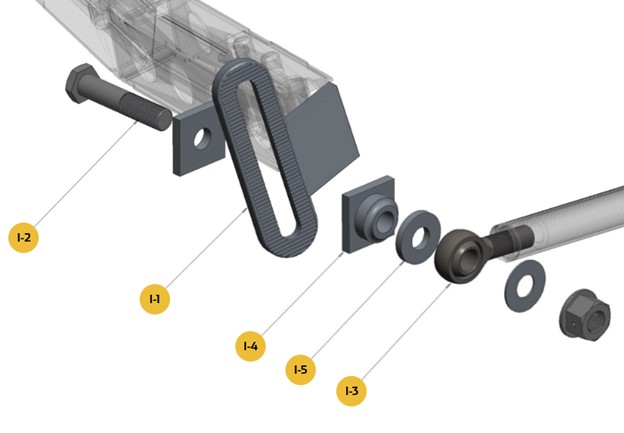

A single bolt (I-2) runs through the mounting plate on the truck arm (I-1), the serrated locating plate (I-4), a spacer (I-5), and the rod end heim (I-3). The bolt itself can be a minimum of 5/8” or a maximum of 3/4” in diameter and the material is not specified. Obviously, a smaller bolt will allow for more flexing. The tolerances between all part interfaces can be a maximum of 0.020”.

The length of the bolt is not specified but is defined by the distance between the center of the heim joint (I-3) and the rear face of the mounting bracket (I-1). A spacer (I-5) can be fit between the heim and the mounting bracket (I-2) to put the heim anywhere from flush with the bracket to 2” away from it. A longer bolt will flex more, but there are numerous ways to skin a cat. A 3/4” bolt with 2” of spacing could be run just as easily as a 5/8” bolt with 1” of spacing. It’s all about getting the rear end to move while not making the car uncomfortable to drive.

Neither the minimum torque on the nut securing the assembly, nor the type of nut is specified but is instead regulated by a team’s confidence in it to not fall apart. Less torque is more skew but also a less stable racecar. More torque is less skew but gives the driver a much more consistent feel.

Qualifying usually gives us a good visual indication of how much teams are deflecting their rear suspension. A qualifying lap will put the car under the highest amount of lateral load at any point during the weekend. If a team has done their job properly, there should be just a whisper of tire smoke as the left rear tire kisses the fender through the corner. Watch below as Chandler Smith qualifies his Xfinity series car on the pole at Las Vegas Motor Speedway. You can see the slight tire rub at both ends of the race track, but pay close attention to how much the left rear tire moves as the car enters the back straightaway and the lateral force is removed. There is a nice close-up shot of the left rear tire at the end of the clip.

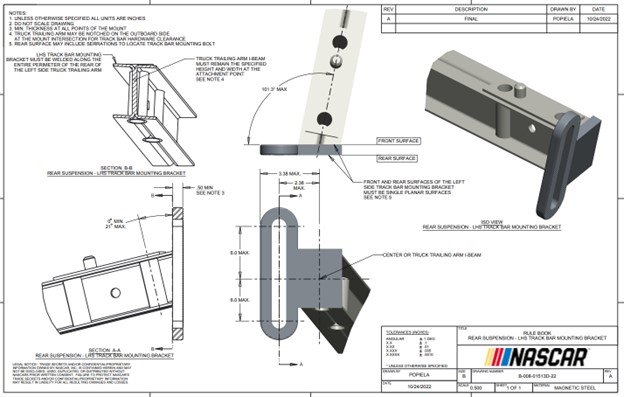

A lot of freedom is given in terms of designing the left side track bar mount which must be made of magnetic steel and conform to the following drawing.

The mounting height of the truck arms is also a vital consideration for teams and can be used to create more dynamic skew when cornering. The mounting brackets are under the center of the chassis, blue #2, in the top illustration. The mounting height of each truck arm is adjustable, and the mounts are slotted so that the arms can be pulled fore and aft using slugs.

Imagine the truck arm is the radius of this circle, and the mounting bracket about which it pivots is the center of the circle with the wheel at the end of the radius on the circle’s circumference. Let’s start our hypothetical truck arm out level and represent it with the blue line. If the suspension travels up, the wheel will follow the radius of the circle. We can represent the truck arm in its dynamic position with the yellow line. You can see that the effective radius, or the horizontal distance from wheel to mount has become shorter. This means that the wheel is being pulled forward in suspension travel.

The opposite is true if the truck arm starts out with the front pivot higher than the rear end. In this configuration, the arm will become longer as the suspension travels and push the wheel backward. This is how teams create rear steer in the car to generate more skew. Truck arm split refers to the difference in height between the left side and right side, with the left side being lower on most ovals. If the left rear tire is pulled forward and the right rear tire is pushed backward, the rear end housing will be angled relative to the chassis. As the driver applies the throttle, the rear end of the car will literally be trying to drive around the front end.

Generally speaking, the lower a truck arm is mounted the worse the car’s underbody aerodynamics will be. As air flowing under the body hits the trailing arm it creates turbulence which reduces under-body downforce. The tradeoff is that the car will be producing more side force and over-body downforce thanks to the skew. Where the balance between under and over-body downforce lies is open to interpretation and up to the teams to decide upon.

On a circle track car, the rear springs also have different purposes. The left rear spring is used to adjust balance and the right rear spring is used to control suspension travel. A stiffer left rear spring creates understeer by holding more dynamic cross-weight in the car and a softer left rear spring does the opposite. Teams often utilize spring rubbers to change the rate of the left rear spring during a race to act as a balance adjustment.

The right rear spring can either be linear or progressive. A linear spring is fairly straightforward. It is a metal coil spring with a rate that acts linearly throughout its range of travel and is normally between 500 and 2,000lb/in. Progressive springs are a bit more complicated. These are what is often referred to as a “rubbered up” right rear, because all of the coils have spring rubbers jammed in them which makes the spring rate get progressively stiffer.

A progressive spring usually starts with a base rate between 100 and 500lbs/in and can be as stiff as 4,000lb/in when the spring has been fully compressed onto the rubbers. These rubbers come in a variety of thicknesses and stiffnesses. Dozens of rate and travel combinations can be made out of a single spring. Let’s graph this out and you’ll begin to see what I’m talking about. The units are arbitrary as I just graphed out y = 50x vs x^2 but we can pretend it’s a spring graph and I won’t get in any trouble at work, lol. On a spring graph, the Y axis represents force and the X axis represents displacement, or how far the spring has been compressed.

You can see that the two lines intersect at 2500 which we can pretend is 2500 pounds of spring force. This is roughly what would be seen at an intermediate racetrack, but let’s call that our maximum force for this example. Let’s also call 500 pounds of spring force the baseline straightaway load. You can see that the linear spring, blue line, would be compressed only 10 arbitrary units at this straightaway force and the progressive spring, red curve, will be compressed 22 arbitrary units. If the spring is compressed more that means that the car will be riding lower.

From this example, we can conclude that a car with a progressive spring will have a lower rear ride height on the straightaway than that of a car with a linear spring despite both cars having the same ride height at maximum load in the corner. While there are certainly aerodynamic considerations regarding the pitch of the car, the progressive spring will mechanically shift the balance towards understeer on corner entry and exit. If you remember from earlier, the right side of the track bar is connected to the chassis and its center point height is the height of the rear roll center. With the chassis riding lower at lighter vertical loads during corner entry and exit, the rear roll center of the car will be lowered which induces understeer. This can allow the team to run a balance shifted more towards oversteer in the center of the corner without having to worry about the driver feeling insecure getting into or off of the corner. The tradeoff is that the driver will have to deal with a much stiffer rate of right rear spring once the car is loaded up into the banking.

A Good Example Of How Tricky This Gets

There have been a number of historical “innovations” in the name of creating skew, starting most famously with the No. 77 Penske Racing Dodge driven by Sam Hornish Jr in the 2008 All-Star Race. Penske built their car with the rear end housing installed sideways, meaning that the car would crab walk around the entire racetrack.

The car’s advantage was so significant that NASCAR effectively banned the practice after just one race with new rules regarding rear-end installation angle and how the wheels could be positioned on the axles. It’s impossible for teams to unlearn what made a car go faster,r though. The genie cannot be put back in the bottle. The era of chasing skew was officially here and a new game of cat and mouse between teams and rule makers began. Teams quickly began experimenting with adding toe to the snouts of the rear-end housing, but this required a significant reworking of the axles and hubs which are not meant to be run at an angle.

Teams also began experimenting with bushings in the truck arm mounts, designing the left side to give more than the right side, allowing the wheelbase to shorten under load. The bushings could also be used to increase rear traction and help a driver accelerate out of a corner. You can see a display of the different types of bushings that teams used to run below from a 2009 practice session broadcast.

During the 2012 season, Cup series teams were still allowed to run a rear sway bar. Hendrick Motorsports began mounting their rear sway bars with the arms angled in a way that preloaded the rear end housing and pushed the left rear wheel forward and the right rear backward when under load on track. The practice quickly spread through the garage before NASCAR made a mid-season rules update to rein the teams back in prior to racing at Kentucky Motor Speedway in June. Before this update, the installation angle of the rear sway bar arms was not regulated, but the update specified that they must be perpendicular to the ground plane.

Hendrick’s setups were not “illegal” during its recent hot streak, when it won five of six events (including the All-Star Race) prior to Sonoma. But the team had creatively found something with the sway bars that worked within the rules, and other teams began to notice and follow suit.

During the recent Michigan race won by Hendrick’s Dale Earnhardt Jr., the Richard Childress Racing cars each used the angled sway bar as part of their setups for the first time (Stewart-Haas Racing cars, which share setup information with Hendrick, were rumored to be using it as well).

“I think everybody has caught on to what they were doing with the bars…and everybody was getting ready to venture down that road and spend a lot of time (in that area),” RCR’s Kevin Harvick said last week. “There is some significant speed in that particular package.”

- Jeff Gluck for SB Nation June 28, 2012

Rear sway bars were outlawed entirely during the 2015 season.

Prior to the 2017 season, NASCAR implemented a rule stating that the static rear skew during inspection must be 0 degrees. This meant that the left rear wheel could not be toed in and the right rear wheel could not be toed out. Once again though, the magic genie of skew refused to go back in the bottle. Teams began experimenting with part tolerances and seeing how low of torques they could run on parts like the u-bolts and track bar bolt in order to gain compliance and therefore skew.

The Penske cars appeared to be the most aggressive with this and picked up several penalties during the season. The #2 car driven by Brad Keselowski was given a 35-point penalty and a three-race crew chief suspension for having too much rear skew in post-race inspection at Phoenix early in the season. They then discovered that if they had the drivers aggressively weave and brake in a certain manner on the cool-down lap the suspension would work its way into a position that would pass inspection. Penske driver Joey Logano was penalized with the loss of 30 minutes of practice at Richmond Raceway for doing this on his cool-down lap the week prior at Bristol Motor Speedway.

Hilariously enough, Logano was also disqualified from that Richmond race for rear suspension violations found in post-race inspection. NASCAR ruled that their truck arm was effectively unattached to the rear end housing as they had a 1/32” (0.032”) gap on both sides of the lowering block that sits between the rear end housing and the truck arm. The current rule is now set at a maximum 0.010” gap between all components.

Auto racing is, at its core, a cat-and-mouse game between the teams who try to go faster and the regulators who try to hold them back. Speed exists in gray areas where the rules aren’t specific, or a certain dimension is left too loosely defined. Every new rules bulletin is read by hundreds of engineers all obsessively trying to find a hidden advantage in the wording.

Top photo: Stellantis, Depositphotos.com

Not a circle track thing, but: I had an issue once with big dynamic toe changes on track, and it was scary! We were doing endurance racing at Willow Springs. I had just gotten into the car, and found that in turn 8 (a long, fast, somewhat lumpy right) the car had a weird “pivot” feel on turn-in and also felt unstable in the lumpy areas. After two laps of this, I brought the car in and insisted that something must be broken in the rear suspension. The guys took a look and found that the rear lateral link bolts were loose! The rear was a Chapman strut with two lateral links & a trailing link per side (Dodge neon) type. They tightened the shit out of the bolts and we continued. I talked to the previous driver after the race – he said that he noticed the “pivot” but found it helpful! I guess he was a born NASCAR driver!

You can see the chassis moving around on the rear axle when they’re doing warm-up wiggles. Always wondered how they got just the right amount of movement.

Glad to see you back and good luck at Daytona!

Left and right relative to what?! This is why “driver’s side” and “passenger side” were coined.

Even on a RHD car the left front is still the left front, no?

Are you looking at the car, or are you inside the car? Left and right are relative to your POV.

Yes but the car itself only has one left front regardless of perspective. I guess I could have clarified that

Generally when talking about “a cars” left or right side you would use the left or right from the perspective of a driver.

This also eliminates confusion with RHD/LHD cars if one used “drivers side” instead.

I think that even NASCAR fans know that the car coming towards them is turning left, because it’s going to the right.

That’s what the terms port and starboard are for, they’re always relative to the vehicle, not the observer.

Rarely used for cars though I admit.

It’s great to see your pieces again Aedan – though now I have two things to look forward to when the racing season gets underway again!

This reminds me I’d love a piece eventually on what tech is actually like. We hear about it all the time (usually the next day after someone loses a podium, like after the other Daytona race), but an insider’s overview would give me something to visualize.

I’ll put that on the to do list

Yesssss more deep dives, we had a dry spell there. I’ma have to read this in a bit but I wanted to chime in early to say I’m happy to see this

A bit of a busy off season, but I’m back and glad you’re excited about it

Great article. It will be a sad day when the xfinity cars have to go to a next gen chassis

Hopefully never

Great read as always Aedan. Sometimes I wonder what’s even left for teams to find, but then I’m constantly surprised when I hear about it. The fascinating stuff for me seems to be the aero manipulation and adjusting paint schemes to trick the OSS into not finding the surface exploited. I can’t imagine there’s too much of that anymore with composite bodies in 2/3 top series.

You would be massively surprised on that one

The delight of NASCAR through the ages is how part of the game is about how close you can get to cheating while technically following the rules.

It’s definitely the special sauce that makes any form of spec racing extra enjoyable to follow and learn more about.

We love the gray areas

I love reading this stuff too. The foundation is an idea so goofy that you think it was cooked up by some ole boys in a garage with beers involved. This is followed by the most exacting scientific/engineering investigation. Those same boys are now probably working on an airplane with staggered wings. This would be for great Circle routes, right?

Having lived the mid 10’s trackbar mount wars, good job summing it up. It is hard to accurately describe the amount of effort that was put in to designing those mounts, then redesigning those mounts to try to catch up with tricks being found by other teams around the garage as well as trying to take advantage of whatever NASCAR tried to come up with each week to try to stop it. Was truly a fun challenge as a design engineer.

Glad to read this Aedan, and happy that you are back again. Thanks.

Thanks for reading!

I believe with the current “Next Gen” Cup car the toe angle can be set independently for each tire if I’m not mistaken? Within limits of course.

Yes they have a fully independent rear suspension and can set static toe using toe links

Watt’s linkages have been around forever, replacing the old Panhard bar. I appreciate the unique circle track advantage the Panhard bar gives, and the engineering that goes into maximizing it.

Road courses are a slightly different story haha

I bet… Likely a Watt’s would be better there! I’m an engineer by trade and training. Have a relative works for Penske.

This is wonderful stuff, Aedan. I’ve always scoffed when F1 types piss on NASCAR, saying it’s Freddie Flintstone. But the engineering and sweat equity that NASCAR teams pour into this minutiae is just staggering, and puts F1 and it’s ironclad rule book to shame.

Thank you!

A cup car is as well engineered for it’s purpose as an IndyCar or FI racer. Rule books set the limits.

You can throw in LeMans/endurance, and NHRA drag racing too. At the top tier, they’re all doing maximum engineering.

Absolutely, the best minds are at the top tier of any sport or endeavor.

Key is fitting the mind to the endeavor…

Actually the limit is how on the ball the inspectors are.

In case anyone is curious where the name comes from, the design of the truck arm rear suspension is based on that of the 1963(?)-1972 Chevrolet/GMC C-10/15 2wd pickup truck, which was adapted to the cars as fabricated frames began replacing reinforced stock frames as the production cars Cup cars were based on went from perimeter frame construction to unibody.

You are spot on

Big, as the kids are wont to say, thank