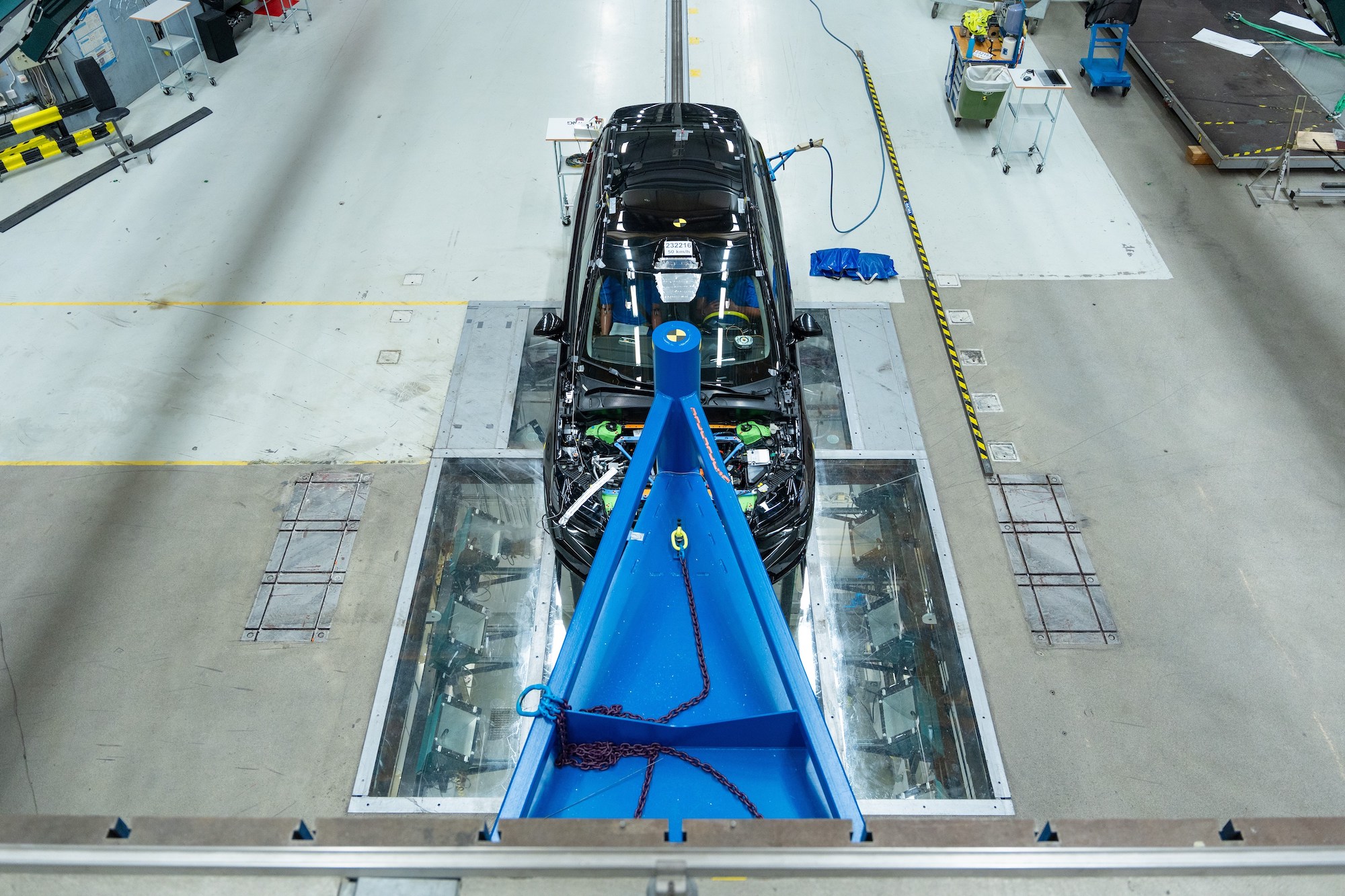

First, the overhead lights go very bright. Then a 90-second countdown begins, initially in 30-second increments, then five-second ones. At 0, a black Volvo SUV hurtles into view and rams dead center into an 850-ton cement barrier. The car is hoodless to better serve the suite of overhead and underfloor cameras, which record every nanosecond from multiple angles. But chunks of metal, glass, and plastic spew from the front end as the vehicle ricochets backward a full car length.

A huddle of technicians in protective gear emerges immediately and begins taking photos and examining the color-coded sensors and under-hood components. One places a drip pan under the car’s front end. But no fluids seem to leak out. This is because the SUV being tested, the all-new Volvo EX90, is a battery-electric vehicle, and ignitable liquid fuel is not an issue.

“For ICE tests, we use a solvent, dyed, which is a fluid that is non-flammable but has the same density as fuel,” Thomas Broberg, Volvo’s senior technical advisor for safety, told me after the wreck. “And the car would be powered up, and the fuel system pressurized, though the tank wouldn’t be absolutely full.” This process allows the Safety team to note any fuel leaks, and to remediate them before things get sparky.

You’d think fissures like these would happen all the time. But, due to the isolation of most modern gas tanks, such breaches are quite uncommon. “Gas tanks are usually behind or around the rear axle,” says Raul Arbelaez, the vice president of the Vehicle Research Center at the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. “So they tend to be pretty well protected. Plus, just because a gas tank is ruptured—let’s say something comes up underneath the vehicle and punctures the gas tank—the resulting fuel leak doesn’t necessarily mean you’re going to have a fire.”

Moreover, tactics for hardening this volatile cell have been honed over 135 years of automotive wreckage. “With gas tanks, we’ve had decades and decades to learn from real-world data to see where we can make improvements,” Arbelaez says. Testing frontal crashes with internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles also involves more potential debris, and deformity, since the hoods of those cars house engines, transmissions, radiators, and exhausts. While these components could potentially become projectiles that enter the cabin and cause injury to occupants, they are often used to dissipate and distribute impact forces. “In some cases, you could use some of that engine block and transmission to work as some of the structure that you rely on,” Arbelaez says.

EV crash tests host some significant differences. Like an ICE vehicle, they have a dense and volatile onboard fuel source that must be monitored. But instead of providing instant spills and sparks, EV batteries have sneakier tendencies.

The batteries are encased in an extremely hardened shell. Still, because it generally runs the length of the passenger compartment, it is more susceptible to rupture in a broader range of crashes than a gas tank is in a comparable ICE vehicle. “It’s a lot of energy stored in one place that needs to be protected from the inside and out—from a chemistry level up to a complete vehicle level,” says Broberg. “So, in the EX90, if you take the complete vehicle level, we have transfer members inside, between the modules, to dissipate the loads, for instance, in a side impact. If you have something in the front end where you’re not engaging the load-bearing structure of the car because you’re missing them, how does that affect the electrical system? And then on the module? And so on, on a complete battery level.”

When a significant wreck occurs, the first concern is a massive discharging of electrical energy. “We need to be able to monitor the battery and ensure that, immediately after an electric vehicle crash, there’s electrical isolation,” says Arbelaez. “So that when our technicians approach the vehicle, or in a real crash, somebody in the vehicle doesn’t suffer from high voltage electrical risk. We don’t want electrocution.”

The next issue, correlative to shorting out, is what the car companies call “thermal runaway,” an overheating that could lead to a fire. To monitor for such events, testers add a variety of instruments to the cells. “We place thermocouples along the battery compartment,” Arbelaez says. “We use thermal imaging cameras to really monitor where that battery temperature is, relative to ambient temperature.” And if they notice an increase, they have tactics that come into play, up to and including removal of the vehicle from the facility. “We have a forklift with plastic electric isolation sleeves on the forks,” Arbelaez says, “The exhaust fans get turned on, and any guests in the facility are escorted out, and we open up garage doors and pull the vehicle outside. The fire department is waiting outside for us for these electric vehicle tests.”

Special meters needed to be developed to aptly measure the voltages on which these vehicles run. “Long ago, someone here said, obviously, if we’re going to crash test batteries, we need to drain the energy out of it. This is a lot of stored energy. What’s the procedure?” says Åsa Haglund, the director of Volvo’s Safety Center. “So we designed the best procedure we could. We left it [the crashed car] three days or something. And then we were going to check, just to be sure. And we bring out our voltmeter. And that one vaporized, pretty much. And they realized, oh, there’s still a lot of energy stored in this battery, and we need different equipment because this is not gauged to this type of energies.”

Unlike an explosion in an ICE vehicle, which typically occurs shortly after a crash, EVs can continue to escalate toward runaway long after impact. So IIHS testers continue to isolate the vehicle and monitor that temperature. “For at least a couple of weeks after the crash, we store the vehicles outside in a dedicated electric vehicle shed,” Arbelaez says. “Some of these events can take days or in some cases weeks for that short to build up enough temperature to actually cause a fire.”

In order to limit the incidence of such brooding infernos, Volvo and the IIHS both test their EVs with onboard cells at a diminished capacity. “Instead of running the battery at 100% or 95%, we reduce that state of charge to 15%,” says Arbelaez. “So there’s still enough energy in the battery to cause electrical shock and thermal runaway, but it’s at a reduced state, so it doesn’t happen as quickly. And if there is a short that can lead to thermal runaway. It will take longer to get there, thereby ensuring safety of our facility and our staff.”

EVs often don’t have much junk in their funk, so one might think they would be more dangerous in a frontal crash, leaving them dangling unprotected like the front seat passengers in a VW Type 2. But this blank area can actually be engineered to the occupants’ advantage. “If you have more space, then you can make some of that material softer and really shape the way you want some of the vehicle deformation and impact pulses to move in the crash,” Arbelaez says. “Again, it’s not better or worse. I think it’s just different.”

Because first responders are just gaining practice in dealing with EV crashes in the real world, Volvo’s safety team is deeply involved with training and disseminating best practices protocols to these emergency services personnel. “When we crash our cars, rescue services come here and try their procedures on newly crushed cars to see if it works, which is very useful for both sides,” says Haglund.

The company even designs special crashes for this cohort, to test the mettle (and metal) of its latest safety cell structures. “Not long ago, the rescue services were kind of complaining that modern cars are so good at crashing, they don’t see any really deformed cars that are hard to get into anymore,” Haglund says. “So we hoisted a bunch of cars, not just EVs, up in cranes, and dropped them from 100 feet onto offset concrete barriers to make sure they were really broken. And then, that became something really juicy for the rescue services to tear into.”

Brett Berk is New York City-based freelance writer who covers art, business, and culture, especially as they relate to and connect with the automobile. His writing currently appears regularly in Architectural Digest, Car and Driver, GQ, The New York Times, Road & Track, and Vanity Fair, and he is co-author of the Phaidon book “The Atlas of Car Design.”

Speaking of Volvo, and its sister company Polestar. Since Beau is associated with this site and Galpin. I had to go to the Polestar dealer for coolant, the closest one is Galpin, i needed to check what hours they are open, i googled “polestar galpin”, clicked on the 1st link directing me to their website, navigated to parts and service, then to parts center. It clearly shows it is open on Sunday, i arrived today for it to be closed. There are multiple versions of the site, others show different information, but from that search and the site i was directed to, it had the wrong info. Absolute waste of time.

It’s pretty common for dealers to have different hours for sales vs service, and for service to be closed on weekends. Looking at Galpin’s site, that seems to be the case. Sales 7 days a week, parts and service Monday to Saturday.

I agree that’s why I was so excited to see that it showed open. Like I mentioned above, they have 2-3 websites and some show different info. I went to the dealer and reproduced what I saw and the guy working at the parts dept was whoa I should show that to someone.

Go here and you’ll see it is open Sunday https://www.galpin.com/parts-center/.

I don’t know the speeds that those two crash test Volvo EX90s were going, but they both look to have protected their passenger cell area very well. The lack of intrusion into the driver’s door area when the black car is getting partially bisected by an immovable pole is very impressive.

My daily is a first-gen XC90 which is a completely different vehicle from the EX90 of course, related to it only by nomenclature. At the time, the XC90 was Volvo’s biggest passenger vehicle (not counting commercial trucks, etc…) and I put up with it’s modest average city MPG of 16 because aside from being comfortable and roomy, this car feels really safe. I’d not want to test the veracity of that feeling, but if the odds say you’re going to get t-boned in an intersection by a stolen Prius going twice the speed limit as it’s pursued by LAPD, better that it happens in a honking big Volvo XC90 SUV IMO. It really feels as if it’d go the extra mile to protect its occupants.

BTW, though the XC90 was the biggest passenger Volvo at the time (2000s) by modern standards it’s not really all that huge. I went car shopping w/a neighbor yesterday and she bought a new Toyota Rav4 (in that lovely shade they call Blueprint) and while I was standing next to one in the dealer’s showroom on Hollywood Blvd., it seems as if the Rav4 has now grown so large that it’s probably within inches of my old XC90 in most dimensions, and perhaps less than a foot shorter lengthwise. The Rav4 is the smallest Toyota crossover currently available, along with the cheaper (and likely just a smidge smaller) Corolla Cross.

Vehicles have really grown in less than two decades… one of the smallest Toyota SUVs is now almost as large as the biggest Volvo SUV was 20 years ago. This is likely an American-market thing, as I imagine there are smaller Toyotas to be had in European and Asian markets.

Good read. Really shows how much we take for granted about the level of background work put into modern vehicles, and the kinds of questions nobody was even aware to ask.

Interested to know how much, if any, of this was done by that American electric car company, or if they just unleashed their product on the road and said “good luck, First Responders!”

…and Elon, who spent NO time in Soweto, has no junk in his funk at ALL!

Like… They are heavier? And the energy storage units and driving components are placed somewhere else?

Commonly, voltmeters are good to 600 volts on the AC side to deal with 460/480. But it occurs to me I have no idea how high my Fieldpiece can handle on the DC side because 5 & 24 are common controls voltage in HVAC.

I’ve seen video of knockoff meters faulting: not something I want to try in person. Good article-and always nice to see a fresh byline. Welcome!

The voltage limit wouldn’t have occurred to me! I think mine is good for 600 as well. 800 could get… kinetic.

This is really interesting! I laughed hard at their fried multimeter.

And i have a question.Are air fires a common problem with lithium cells in cars?These happen when cells are punctured and are a different thing to thermal runaway

Usually, whatever does the puncturing also creates a short circuit between the electrode stack layers, which then generates heat as that cell (and any others in parallel with it) dump their current through that short. In turn, that creates a bigger short by melting the separator (between cathode & electrode, provides the electrical isolation to the cell) between other layers within the cell, generating more heat, until the whole mess gets hot enough to ignite. This can take seconds or it can take days, or it can not happen at all, depending on the batteries state of charge, the severity of the short/puncture, the cell chemistry, initial temperature etc.

Pure lithium reacts violently with water, and will burn in air (as will Mg, Cu, Al, Fe etc), but it rarely exists in Li ion batteries – its almost always captured as compounds or trapped within the anode or cathode. Its not the exposure to air that will start a thermal runaway.

I’m curious how many thermal runaway events have happened during crash testing. I have been under the impression these events are rare. Are they being overly cautious or is this something they see frequently?

Also: “we hoisted a bunch of cars, not just EVs, up in cranes, and dropped them from 100 feet onto offset concrete barriers to make sure they were really broken.” I would love to see videos of these tests. My initial thought is that these cars would be completely obliterated, but I found an online calculator that says they would be going ~55 mph at impact, so maybe the impact isn’t as dramatic as I am expecting?

On the original Top Gear, they put a Toyota Hilux on a multi-story building about to be demolished, and after it hit the ground (falling straight down from the top, more or less), and using only “basic tools” for repair–it was running again.

I doubt this stuff is thought of in normal testing and obviously that’s an extreme example, but I would assume that being dropped already has the big advantage of using the tires and suspension components as buffers.

I would think that in a side impact crash the battery cage would take some deformation so it is surprising that cell rupture is so rare. Since EVs spend so much time charging, that is the most likely fire scenario and it gets all the attention. I wonder if there is significant real world data yet for analysis of EV fire risk by crash angle and severity.

Sadly, the biggest producer of EV cars in the last decade does have an unfortunate habit of fighting tooth and claw against sharing any data.

This was interesting to read