On December 2, 2023, a specially built Porsche 911, driven by Romain Dumas, achieved a world record by driving up the west ridge of mount Ojos del Salado, one of the highest volcanoes in the Chilean Andes. Reaching a height of 22,093 feet, the car had to drive up some of the most rugged and unforgiving terrain imaginable.

Clearly, a regular 911 would be completely incapable of achieving such a feat, so Porsche designed a revolutionary new suspension system — called the “Warp Connector” — and built it into a very special car the brand named Edith.

To learn more about Edith and what makes this suspension so special, David Tracy and I met with Luke Vandezande, Public Relations Spokesperson for Porsche USA, and Sven Schaarschmidt, Lead Engineer, Sports Car Front Axles. What we learned during our discussion made it clear why the car was able to achieve such a record setting drive but also why this suspension will probably never see use in any other vehicle.

[Ed Note: Our friends at Tangent Vector produced the movie “Edith: Volcano Ascent” showing the entire world record attempt. It’s one of the most beautifully shot car-videos you’ll ever see, and the tension the team feels as it tries to accomplish the impossible is truly palpable. Bravo! -DT].

Why Wouldn’t A Regular Porsche 911 Suspension Work?

Before I introduce you to Edith, let’s talk about why a standard Porsche 911 (or even the 911 Dakar shown above) would make for a terrible hard-core off-roader, and why Porsche even bothered to design the Warp Connector in the first place.

The 911, like all modern sports cars (and most every other car these days) uses independent suspension at all four corners and is designed to operate on relatively smooth roads. This means the suspension is designed to move up and down a fairly small amount, usually a total of about 150 mm (6″) at most. That’s fine for regular roads, but when you go off-roading, the surfaces are definitely not smooth, and the wheels have to be able to move up and down much further to get over the rocks and through the holes of a dirt road.

In addition, sports cars sit very close to the ground, so there’s not enough clearance to drive over the roughness of a dirt road. Lastly, independent suspensions have fairly low roll centers to prevent jacking in corners and tire scrub during ride events. Solid axle suspensions, on the other hand, have much higher roll centers without suffering the jacking and ride issues independent designs have. This is especially true for suspensions designed for high speed cornering and handling, like the 911’s. I talk about this in much greater detail in my post comparing solid axles and independent suspensions, but the point is that a standard 911 independent suspension would not have provided the ground clearance nor the suspension travel needed for an off-road vehicle.

Porsche engineers solved these problems by designing a completely new suspension that allows for significantly more travel, and by using portal axles that allow the wheels to be located much lower on the suspension, thereby “pushing” the vehicle up for more clearance. The car also uses much larger tires, as you can see in the photo above.

All these changes made sure Edith sits high above the ground and has the necessary suspension travel to get over the big undulations you might find off-road. Can you imagine a standard 911 doing this:

For those of you familiar with off-road vehicles, you probably know that solid axle-equipped machines (Jeep Wranglers, old Land Rover Defenders, old Land Cruisers) tend to perform best when rock crawling, as the axles are able to articulate so much that they keep all the tires on the ground, propelling the vehicle forward. The downside, of course, is that such a suspension typically allows for loads of “roll,” which isn’t great for handling. (Disconnecting sway bars when off-road helps, but the nature of a solid axle puts the vehicles “roll center” so high that you’re going to get roll in corners).

The Warp Connector is meant to offer similar suspension behavior as a solid axle, but without that “roll” drawback. In other words, the suspension gives you solid axle-like cross articulation while at the same time giving infinite roll stiffness on-road. It basically takes the roll center issue off the table as far as articulation is concerned. You could build a car with a super flexy independent suspension and no Warp Connector, but to achieve the cross articulation/RTI score you want, you’d end up with high roll centers just like you do on a solid axle suspension (and this can have jacking and ride problems). Using a sway bar disconnect like many IFS/IRS off-roaders do can help. The Warp Connector, within the limits of suspension travel, gives you near zero cross articulation stiffness (i.e. resistance to flex). It’s even better than solid axles, which still have some cross articulation stiffness.

Anyway, let’s dive into this a bit more.

Let’s Look At Edith’s Hardware

Let’s have a look at some photos David took when Edith was unveiled at Monterey last month. We’ll get into the details of what all this stuff is later. You can see the Warp Connector running down the middle of the cabin here — yes, the Warp Connector is a physical linkage that runs through the car!:

and here:

You can see in the following video the Warp Connector in action over the same big undulations we saw in the video above:

Here is a good view of the front “heave spring,” which I’ll talk about later:

And here is a view of the front suspension showing the portal axle, which basically allows you to drive the wheel from a point higher than its center, essentially pushing the wheel down and thus the vehicle up for more ground clearance:

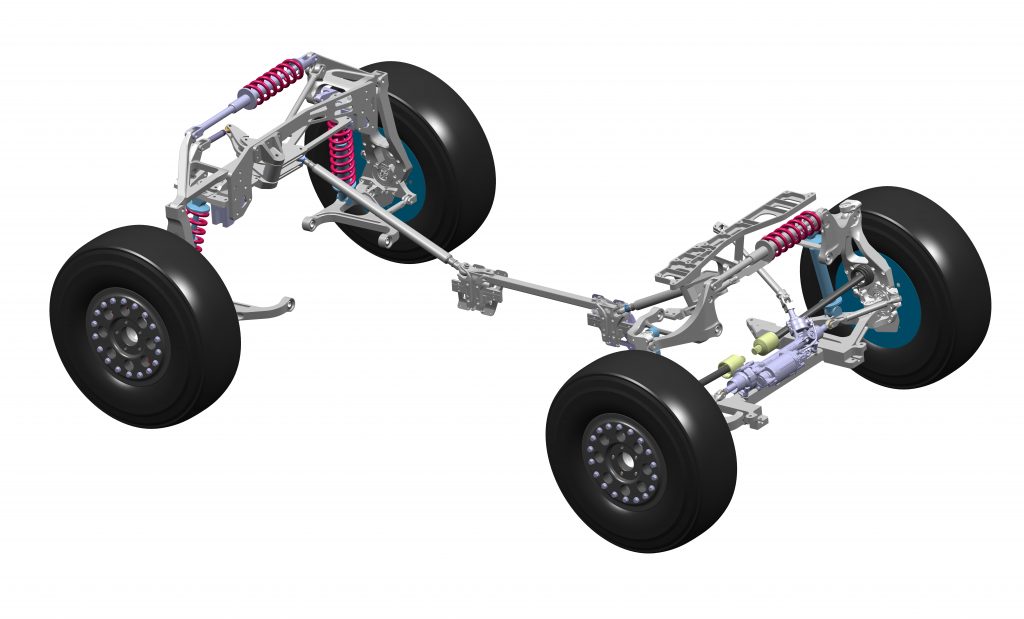

If we stripped away all the other parts of the car and looked at only the suspension, this is what we would see:

The front of the car is to the right in this image.

As I mentioned, Porsche calls this system the Warp Connector suspension, and a couple unusual things stand out immediately. Both suspensions have a horizontal spring spanning between the upper control arms (also called a “heave spring”), there are no normal springs in the front suspension, and there is a strange collection of links running between the front and rear suspensions. It’s this connection between the front and the rear that gives the suspension its name and is the key to making it work.

Originally designed for the 919 racecar, the Warp Connector was an attempt by Porsche to design a suspension system that keeps the load at each of the tires equal. As a car moves down the road, irregularities in the road surface push up and down on each tire. These up and down forces change the load at each tire, and as the load at each tire changes, so does its grip. If the car encounters a bump in the road while cornering, for instance, the grip level at the tire that encountered the bump would momentarily increase while the grip on the other tires that didn’t get pushed up would decrease slightly. On a race track this wouldn’t be a huge problem since the surfaces tend to be quite smooth, but on a road course, this could be a big deal. Porsche designed the Warp Connector as a way to allow the front and rear suspensions to move together over such a bump and maintain similar pressures at each tire, thereby maximizing grip.

In the 919 it didn’t quite work out that way for reasons we’ll talk about later, which is why you haven’t seen this design in any Porsche race car. However, when a skunkworks team was formed a while later to build a car for a record breaking altitude attempt, engineers felt that the Warp Connector might be the perfect design for an ultimate off-roader.

Prodigious Articulation, But Without The Drawbacks

One of the biggest challenges off-road vehicles face is trying to keep all four tires in contact with the ground as much as possible in all sorts of terrain. Since driving on flat ground is not all that interesting, a lot of off-roading is done driving through ditches and over rocks and boulders. This requires the front and rear suspensions to articulate in opposite directions so that all four tires stay in contact with the ground. Like this:

In the case of a Jeep like the one above, however, the wheels that are being pushed up (the front left and rear right in this case) will carry the majority of the weight of the vehicle, and in extreme cases one or both of the other wheels might even be hanging in the air. That means that there are really only two wheels that can deliver significant power to the ground, not four.

But what if there were a way of allowing extreme cross articulation like shown by the Jeep, while still allowing all four wheels to equally carry the weight of the car and thereby also provide maximum traction? This is where the Warp Connector comes in.

We’ll start by looking at how the suspension moves when all four wheels move up and down at the same time:

Notice how the front and rear horizontal heave springs compress when the wheels move up and uncompress as the wheels move down. This is typically how a heave spring works. It gets compressed during upward suspension movement and un-compressed during downward movement. Nothing particularly special here.

The other thing to notice here is that the Warp Connector tying the front and rear suspensions together doesn’t seem to be doing anything at all. The reason for this is the way it is connected to each suspension. If we zoom in to this area, we can see what is happening and it is easiest to do this with the rear:

Let’s look at the individual components:

You can see how the upper control arms are connected to the heave spring and also how there is a small set of links arranged in what looks very much like a small Watts linkage, similar to what we saw on the rear axle of the Ranger Raptor. Porsche didn’t have a specific name for this mechanism so I’m just going to call it a Watts Link. There’s one in the rear and a very similar one in the front. You can get a good view of the front one here sitting next to the heave spring:

Notice in the video how when both wheels move up and down together, the two small links connected to the upper arms move in opposite directions and the central pivot simply rotates around its central rotation point. As a result, there is no movement of the warp connector rear bell crank. Remember this as we look at the case where the wheels move in opposite directions.

Notice how in this case the warp connector linkages are moving fore and aft as the wheels move up and down. Let’s again zoom in on the rear suspension to see what’s going on:

Now we see a very different type of motion happening. Since the upper control arms are now moving in different directions, the two small links in the Watts Link are each moving in the same direction, which forces the central pivot to move with them instead of rotating. This has the effect of forcing the Warp Connector rear bellcrank to rotate and pull on the links connecting to the front suspension.

These links connect to a very similar bell crank at the front suspension, and that other small watts linkage (shown in that photo David took above) connecting to the front upper control arms. The effect is that when the rear wheels move up and down in opposite directions, it forces the front wheels to also move in opposite directions but in reverse. What I mean by that is that when the right rear wheel moves up and the left rear wheel moves down, it forces the left front wheel to move up and the right front wheel to move down.

Notice that both front and rear heave springs are not being compressed. They are simply moving side to side. This means there is very little resistance to this cross articulation, or “warp” motion, unlike in the Jeep shown in the video above above. It’s true that there are normal looking springs in the rear suspension, but Porsche tells us these are really only there to help the re-center the car once the suspension has been deflected, and they are actually quite weak. In theory, they could be removed completely and everything would still work the same.

Since it takes so little force to articulate the suspensions, it also means the load at each tire isn’t changing much at all — exactly what Porsche was trying to achieve. All four wheels maintain the same contact with the ground and therefore none lose traction as long as you don’t exceed the limits of suspension travel.

Sounds great, right? Well, there are some drawbacks to the system.

It’s not all Roses and Butterflies

While the ability to easily articulate the front and rear axles in opposite directions from each other is great, it doesn’t always work out that way. In reality, the front and rear axles encounter things like rocks and ditches at different times. The front will hit the rock or ditch before the rear does and so the front needs to be able to react to it before the rear needs to react. The Warp Connector, being a mechanical device, forces the front and rear suspensions to work together AT THE SAME TIME. When the front suspension encounters an object like a rock or ditch, it forces the rear suspension to react to it immediately even though the rear hasn’t reached it yet. When you are going slowly, this doesn’t pose much of a problem, but when you are traveling at some speed, the result is a vehicle that can react quite violently. You can see it here in this clip:

Notice how when the left front wheel hits the rock, the car jumps up almost rigidly. I can only imagine the impact the driver must had felt. The reason for this is that when the left front wheel hits the rock, it forces that wheel to go up. The heave spring then pushes down on the right front wheel. At the same time, the front suspension pushes on the Warp Connector which pushes on the rear suspension. In the rear, the force from the Warp Connector wants to lift the right rear wheel and push down on the left rear wheel since it is trying to twist the rear axle in the opposite direction from the front. The net effect is that when the left front wheel hits the rock, it pushes down on the right front and left rear wheels. But none of this can happen quickly because there so many parts involved, many of which are quite heavy. If the car is moving at speed and a wheel hits a rock, like in the video, the opposite wheels simply don’t have time to react and the whole car gets launched into the air.

There is a simple way to mitigate this to a degree, which would be to replace one of the rods in the Warp Connector with a spring, and this is under consideration by the Porsche engineers. It would reduce the effectiveness of the whole system somewhat, but it would add some compliance and energy absorption to the system, reducing the tendency to launch upward like we saw, and allowing the wheels to move more independently from each other. During slow rock crawling or ditch traversing maneuvers, this new spring would have little impact, so I think overall it would be a very good modification to the system.

Infinite Roll Stiffness: Is This Good Or Bad? I Haven’t Decided

There is another consequence of the Warp Connector, and I haven’t decided yet if I’m OK with it or not. Since the system forces the axles to articulate in opposite directions, it will prevent them from articulating in the same direction. This could be a problem during cornering when the body wants to roll and both axles need to articulate in the same direction. The system would basically give you infinite roll stiffness and I’m not sure yet if that is a good or bad thing. It might feel great if the car has no roll in a turn but in a traditional suspension, having high roll stiffness is usually accompanied by a nervous ride and one that doesn’t react well when you encounter a bump in the middle of the turn.

I suspect the issue I talked about earlier when a front wheel hits a bump might be an even bigger problem here since the car would be launched into the air in the same way as in the video except that if this happens in a turn, the tires lose their cornering ability. Not a good thing. Of course, adding a spring in the Warp Connector, like was proposed earlier, would probably fix this problem (or at least reduce it) as well.

Although the Porsche engineers didn’t say so, I believe this problem may have been what killed the Warp Connector in the 919 racecar and why we will likely never see it in a Porsche road car. That, plus it is incredibly complex and takes up a ton of space. The system just doesn’t make sense for a road car that is meant to also accommodate passengers and their stuff.

As it turned out, the infinite roll stiffness became an advantage for Edith since they were carrying about 200 Kg of stuff on the roof rack. So much weight located so high up in the vehicle would have made the car very tippy, especially while traversing over angled terrain. A standard suspension (like a flexy independent suspension with a disconnected sway bar) might have caused the car to roll over while the Warp Connector kept things stable.

All in all though, even with its flaws, it is still a very cool system. And it certainly has proven its abilities by driving up some of the most challenging terrain imaginable.

More Images of the epic journey up the volcano:

More images of the Warp Connector:

Wouldn’t this Warp coupler be simpler and have substantially faster reactions with less inertia as well as smoother disconnect/reconnect if they rotated the Watts linkages 90 degrees so that the motion was translated via rotational motion (torque) rather than longitudinal motion? A simple electronic clutch could even translate just some of the force and at various specific rates if desired.

As mentioned by others, a fully hydraulic coupling of each wheel with magneto-rheological control would have the greatest fidelity, but turning the Watts linkages on their sides with a variable electric connection to transmit the torque (like the “e-diff” in many part-time AWD setups) wouldn’t require too much modification.

Impacting a bump with one wheel could either, by coupling to the other Watts link, send the force to the same crosswise pair of wheels as the Porsche setup, by coupling to nothing or to a spring it could absorb most of the impact in that wheel alone, or by coupling to the chassis, it could share some of the load with the suspension of the other wheel on the same axle, directing it towards the heave spring. Depending on whether one expects that bump to soon affect another wheel or not, different force paths could offer a significant benefit.

A torsional setup would seem to add a lot of functionality without losing the original warping ability or completely reengineering an entirely new system. Then again, Porsche ain’t paying us to do their work for them.

This thing is awesome! Where can I watch this documentary when it comes out?

So it’s an interesting idea, and some cool engineering, but I see several major holes.

This is cool because it allows good flex without incurring poor roll stifness and sway for when you’re on the pavement…….. Except this is a dedicated off-road vehicle which never needs to see the pavement. If it had solid axles and a super high roll center it would literally be fine, because this vehicle will never be carving corners.

Yeah, the roll stiffness is nice when you have 200kg of gear on the roof raising your CG, but it’s not like this was gonna tip. It’s a Porsche 911. Even with all the junk on the roof, it still has a lower CG than a lifted Land Cruiser, and you see those bashing Moab all the time.

All this, and the results were not even that good. In the GIF of the car flexing over the whoops, it runs out of flex twice, so you can obviously see the precise limits of its flex.

And its flex is quite bad for a purpose built offroader. What is that, 20° of total flex? If that? All this engineering just to get dunked on by a stock Wrangler with disconnected swaybars. I’m not even joking when I say that my stock F150 can manage that much flex, and that’s with IFS and the stock swaybar.

I’m not one to hate on engineering new things and trying things out just for fun, but when you try it and the results are poor, experiment over. Nothing more we need to learn here, we tried that and we won’t try it again, because it sucked.

Maybe the warp linkage is a good idea and would make for good results on a vehicle that has enough suspension travel to actually utilize it?

All this engineering to basically have a form of non-independent suspension. It is cool though.

This is Porsche so it’s only logical they would overengineer a currywurst if they could.

Excellent article! I was really hoping someone would do a deep dive on the engineering of this car, and here it is!

That is way cool. Mulling on this setup, I have to wonder what would happen going around a washboard corner at the wrong speed? With the large wheel & tire—not to mention the portal axle—that’s a lot of mass changing direction at each corner. I’m having a tough time visualizing it, but I kinda think you’d be losing traction alternately front and back. Would it understeer and wash out of the corner, or oversteer and spin out? Or tesseract-snap into a tiny high-energy point and weep softly?

my head hurts

I’m thinking a lot about those “portal” axles. I would have called it a crop sprayer axle if they hadn’t already come up with a name. There’s some gearing and stuff in there so I would expect novel issues.

Early WV vans had portal axles to lower the gear ratio. Unimogs too, just off the top of my head. They’re a known piece of equipment, so I’d imagine Porsche engineers had plenty of info to go off of.

H1 Hummers did as well, IIRC.

I don’t think portal axles create any problems or unexpected suspension behaviors beyond the effects of the considerable unsprung weight.

I wonder if they could replace the mechanical warp link with a hydraulic circuit. Not only would it be easier to package, but could be more readily adjustable with a variable volume chamber, say stiff at low speeds, loose at high. I ask because I designed something along these lines for a vehicle in an unfinished novel (that might show up in another one if I write that one), but originally planned on a hydraulic circuit, but figured that it might have the issues of this warp system or might not be effective enough. I’m not an engineer and I’m not rich enough to prototype stuff I come up with, so I have to work it out on paper and by guessing. That car also allowed for variable ride height (the origin for the idea), but that’s both unimportant here and I can’t remember the exact mechanism (which didn’t really matter as I don’t detail this stuff in the books as nobody wants to read that, but I don’t want something that’s not at least plausible).

I think a hydraulic system would be the right alternative to all these mechanical linkages.

Hydraulics work excellent for controlled movement.

In my industry (Transit buses) we use them to control the articulated joint in 60ft buses.

It’s basically a big circle bearing with two hydraulic cylinders, 4 sensors, and a valve body in between.

Based on vehicle demand and/or the angle of the joint, the valve body restricts movement of fluid from one cylinder to the other by choosing one of 3 metered orifices. This stiffens or loosens the joint movement.

This is especially important as currently all diesel articulated buses are driven by the 3rd axle in the “trailer” section of the bus.

EV 60fts have the center axle driven by hub motors, so the relationship between the front and rear of the bus changes.

I think you could do some wild things with cross-linked hydraulics in combination with some sort of air spring interlinking.

It’s basically what Citroen did to great effect, which is partly where I got the idea.

I love threads like these, with informed discussion of the merits and drawbacks of mechanical systems in real-world application. You guys are all awesome.

As I was reading the article, I started thinking about the hydropneumatic suspensions in Citroens, and imagining a cross between the Porsche and Citroen system. I figured it’d make some amount of sense to replace the central linkage with a hydraulic system working on the linkages via pistons. Then when Huibert mentioned the possibility of a spring taking up part of the linkage’s duties, I thought about the squishiness inherent in a hydraulic system with gas in the line…

Then lo and behold, I see other people already having the conversation.

The heave spring is quite common in Formula Vee, where the Beetle’s rear swing axle suspension makes the very light, mid-engined formula cars prone to oversteer. They call it a zero-roll rear end, and as the name suggests, it gives the rear zero roll stiffness, leaving all roll work up to the front axle. This settles the car out and enables much earlier throttle application on corner exit. All that said, the warp link sounds like a rock crawler’s dreams come true.

Makes perfect sense to me!

Fantastic technical deep dive Huibert. With all the complication, one has to wonder why they didn’t just hydraulically cross link? Maybe because of the single heave spring it doesn’t work?

I can’t really answer that question but I suspect the added complexity, risk of hydraulic leaks and failures plus that fact that the system had been substantially developed already come into play here.

I’m trying to imagine Porsche engineers deciding against something due to added complexity.

Looks like I’m not the only one to see all these mechanical linkages and think “so it’s a Citroen 2CV with extra steps…”

Would it even be possible to do a magnetorheoligic (SP?) in the warp connector to potentially reduce the way it slams down? Yes, much more complex, and I don’t even know if it’s technically feasible.

I think some sort of spring and damper system in the warp connector would go a long way to making the system more road friendly.

My thought was that going magnetorheologic would be able to stiffen when necessary and be compliant when necessary, versus having to dial in the right spring rate. Kinda giving you the best of both, but I expect a rather significant jump in cost and complexity.

Fantastic article and animation! Immediate thought while reading; Why the hell did they use a physical connection between front and rear? If you replace that with position sensors, and motors or hydraulics, you could leave the cab intact, and also add terrain and speed sensors to actuate.

I have a dream of building a rock crawler with fully articulated hydraulic suspension (height, direction, camber, and speed – controlled independently at all four corners) that is run by a computer using 3D cameras to model the terrain and adjust everything in real time.

Or just go simple Rocker-bogie.

https://science.nasa.gov/mission/mars-2020-perseverance/rover-components/

There’s an RC car built for speed runs that uses a drone stability and active suspension/steering. It works like you’d imagine except instead of prop speed control it controls steering and suspension. No terrain cams though.

That was my question too. If you just wanted to maximise articulation and minimise roll then some kind of hydraulic system seems like it would be the easiest to implement with minimal compromises. Sure, you’d have to add armour to all the hydraulic lines, but if you’re already this deep into things, what does it matter?

I’m assuming that they were looking for an alternative outlet for the design to help offset the R&D costs that were allocated to it for the 919.

This is not a question that I ever expected ever to type. Ever.

Would it not have been simpler and easier to re-engineer the suspension from a Citroen Xantia Activa?

These are the types of questions I like to read ’round here.

Because an extra 350lbs and $100k of development, but mostly because “Not Invented Here”.

The Citroen or some other active or semi-active system does come to mind here. Most truly active systems are not yet fast enough to respond to regular road inputs but off-roading is normally slow enough that I would think a currently existing active system would work. Of course, it would have to work at the altitudes and temperatures you would find at the top of a mountain.

911 with manual transmission and portal axles. It doesn’t get much more petrosexual than that. Hot damn if that was available for production cars. Surely in this safari this and that madness there’s enough potential customers for such.

Altough have to say that that moving suspension component uncovered in the cabin is rather safety third. I would have expected Porsche to have some super fine apparatus over it.

Now now, there’s still more room. It could also be a V10 diesel wagon painted brown. 🙂

Step 1: Buy another V10 Touareg

Step 2: Convert to manual

Step 3: Profit??

Or just one up yourself and try to find a way to buy a Q7 V12 TDI…

I think portal axles alone are like 90% of the thrills. I don’t think there’s any other road going non-military vehicles with portal axles than G-series 4×4 and 6×6 variants.

Also I’ve had manual diesel *wagons (not V10 though, altough not that much of a fan). But no portal axles yet. Closes I’ve got so far were few military vehicles I’ve sat in and few Unimogs and Volvo 303 I’ve seen.

*one was dark red Alfa, and if it was dirty enough, you could have called it brown.

I think the early VW buses are the only road going vehicles using portals that are not a direct adaptation of a military vehicle.

If you’re okay with military-based but not actually owned by the military, there are Unimogs, Pinzgauers, and Hummers.

I was not aware that vw busses had those, that’s interesting. Some VW military vehicles yes.

It doesn’t look like it takes up too much room. You got a 2 door sports car in the first place, they’re not known for their roomie-ness.

It does actually take up a lot of space. With the warp connector running down the tunnel you would need to find another place for all the stuff in the center console, including radio, and climate control system. There would be no second row seats at all, even a 2+2. And where would the cup holder for that big-gulp go?

I believe you have the space for all of those things in said car.

Aww yiss a Huibert article on a super weird suspension. This is certified Good Autopian.