Throughout motorcycle history, companies and inventors have tried to make riding a motorcycle closer to the experience of driving a car. Some of these motorcycles feature roofs, seatbelts, cavernous storage, and a powertrain encased under a body. Many even had automatic transmissions. This concept goes back even further than I initially thought. Back in the early 1920s, you could buy the Ner-A-Car, a motorcycle with an automatic transmission, hub-center steering, and a perimeter frame inspired by a car’s frame. It was marketed as being an “Automobile On Two Wheels” for women, children, men, and anyone else.

Last week, I highlighted a far more recent attempt to blend car technology with motorcycles. The BMW C1 was an ambitious project that saw BMW’s engineers outfitting a scooter with crumple zones, seatbelts, and a safety cell. BMW’s goal was to make a scooter that was as safe as a city car but cheaper to own than paying for a monthly train ticket. Motorcycle history is full of stuff like this from the fully enclosed Carver to all sorts of trikes. In my BMW C1 post, some of you mentioned that there was a motorcycle predating all of this stuff by a whole century. Let’s shine a light on it!

The Ner-A-Car predates all of these motorcycles, and its design still has some value a century later. As luck would have it, I found a 1923 Ner-A-Car when I went to the National Motorcycle Museum on Labor Day.

Blending Cars And Motorcycles

This story takes us back to the early 1900s during a time of experimentation in vehicles. Carl Neracher was born in 1882 and as noted by the New York State Museum, Neracher kicked off his career in vehicles when he was a sales rep for the the Smith Motor Wheel Company, today known as the A. O. Smith Corporation. If that name sounds familiar, it’s because there’s a chance you have one of its water heaters in your home. But back in 1914? The company was known for its bicycle parts and car frames. The Smith Motor Wheel was a gasoline-powered motor that attached to a bicycle as a third wheel.

Neracher would later move to the Cleveland Motorcycle Manufacturing Company, where he would serve as the firm’s chief engineer. At Cleveland, the New York State Museum writes, Neracher designed a transverse-mounted two-stroke single-cylinder engine. The 221cc engine delivered power to the rear wheel of a Cleveland motorcycle through a 90-degree bevel-drive which turned a chain.

Reportedly, the motorcycle saw some success and the Army would use the motorcycle for courier service in World War I. This machine is important as the engine would make a return later on. The New York State Museum notes that after his work at Cleveland, Neracher joined New York’s Essex Motor Truck Company in 1916.

In 1918, Neracher presented a prototype for a new kind of motorcycle. This bike had a low-slung step-through frame, hub-center steering, and an elevated seating position. Mounted behind the front wheel? Neracher’s transverse two-stroke single.

Despite the technology on display, the prototype recycled known technology into something new. As motorcycle history publication the Vintagent reports, hub-steering and step-through chassis were already established back then and was even found in 1904 on the British Tooley’s Patent Bi-Car.

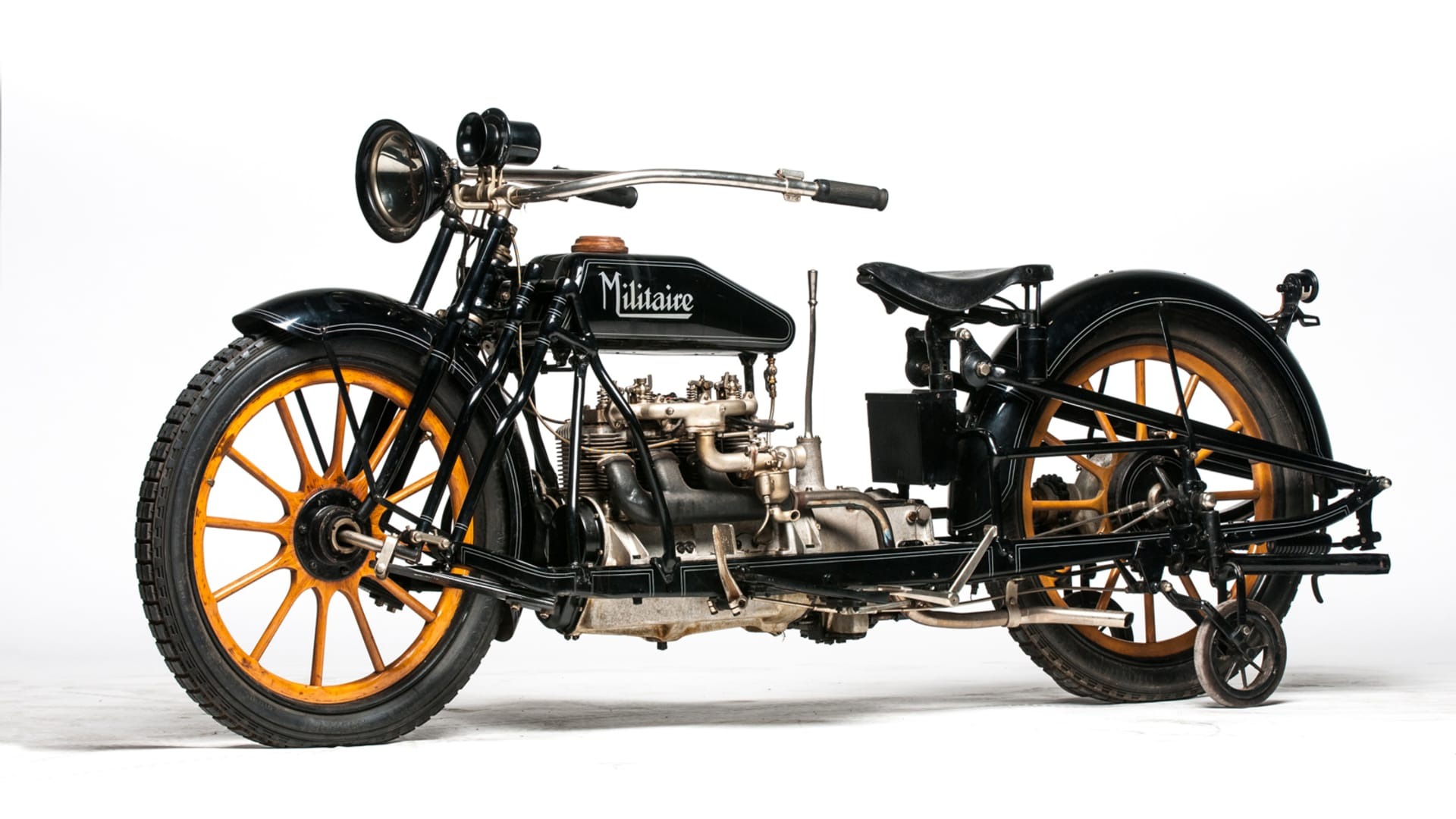

The low frame would also show up in Norman Sinclair’s 1914 Militaire, a motorcycle that was designed to be car-like and so unlike a typical motorcycle that it wasn’t really a motorcycle anymore. The original Militaire sported a steering wheel, which levered girder forks, and an articulated steering neck. That’s not hub-center steering, but what was described as “a pivoted front axle.” Another neat Militaire trick was a set of outriggers that would drop at the push of a pedal, allowing the Militaire rider to stop without putting a foot down. Later Militaires, like the 1915 model above, reverted to a normal handlebar setup.

It’s unclear how many of these older designs inspired the Ner-A-Car, but the Ner-A-Car itself references patents granted to John J. Chapin of the Detroit Bi-Car Company in 1911. According to the New York State Museum, which references a 1911 edition of The Bicycling World, the Detroit Bi-Car was “an attempt to construct a two-wheel vehicle embracing many desirable features of the automobile.” The Detroit Bi-Car was similar to the later Ner-A-Car in that it used a car-style frame, steered its front wheel through linkages, a body of sheet steel, utilized footboards, and a low center of gravity for safety.

Reportedly, few, if any of the Bi-Cars were ever sold. What is clear is that Neracher must have secured a license for the Bi-Car design before putting his own twist on it. The Ner-A-Car Corporation was founded in 1920 in Syracuse, New York and a year later, Neracher applied for a patent for a “Motor Cycle.” United States Patent 1,547,157 was granted to the Ner-A-Car Corporation in 1925. Ner-A-Car’s patent is extensive, including 9 pages of drawings, 13 pages of explanation, and a claimed 98 improvements in motorcycle design. That’s just for the motorcycle’s chassis, not the engine, transmission, or controls.

In the patent image above, you could see the perimeter frame and why Ner-A-Car said it was an “automobile type chassis.”

Nearly A Car

Before Ner-A-Car was founded and before Neracher even chased that patent, he was working on setting up a distribution network. Neracher’s business partner, J. Allan Smith, convinced England’s Sheffield-Simplex Motors manager Harry Powell to sell the Ner-A-Cars in Great Britain and the English colonies. In 1919, the Inter Continental Engineering Company was formed in London with Smith, Neracher, and Powell on the board. Sheffield-Simplex set up a factory and started advertising the Ner-A-Car in 1921.

[Editor’s Note: We’ve actually written about the Ner-A-Car in a different context before! – JT]

Meanwhile, in America, the Ner-A-Car (marketed as the Neracar in America) rolled out onto the floor at the Chicago National Motorcycle, Bicycle and Accessories Show in 1921.

The Ner-A-Car starts with a low perimeter frame. On top of it, a sheet metal body hid the dirty mechanicals from the rider. The front wheel is pushed forward and is turned by a set of linkages manipulated by the handlebars. The rider sits on a high seat and commands the vehicle with a comfortable feet-forward position.

Under the bodywork sits a 221cc two-stroke single making 2.5 HP. There isn’t a transmission connected to it. Instead, a friction wheel was moved between the center and outer edge of the engine’s flywheel, effectively changing the bike’s gear ratio. This setup was operated from a lever with five indents. When the friction wheel is placed near the center of the flywheel, you get a lower speed. When the friction wheel is moved toward the outside of the flywheel, the Ner-A-Car moves faster.

Ner-A-Car advertised a 175-pound weight, a top speed of 35 mph, and fuel economy of 85 to 100 miles per gallon. Further, the company said you could go 300 miles for just a dollar ($18 today). Advertisements said that the Neracar had one of the simplest drivetrains, featuring just six moving parts from the engine’s piston to the rear wheel.

The name of the Ner-A-Car was also a bit of a double entendre as the vehicle was marketed as being nearly a car, but the motorcycle was also quite close to its inventor’s name.

In practice, the Ner-A-Car and its American Neracar sibling had proven to be a stable machine. Apparently, it was so easy to ride and so stable that some stunts included riding Ner-A-Cars while standing up and not touching the bars, riding a Ner-A-Car while handcuffed, and more. Ner-A-Car boasted the vehicle’s low center of gravity and claimed that it was designed so well that even on the roughest roads, skidding would be reduced to a minimum. The Neracar was designed to be so friendly to new riders that there was debate within Ner-A-Car about whether 35 mph was too fast of a top speed.

In its advertising, Ner-A-Car said the motorcycle was “Motoring On Two Wheels” and “An Automobile On Two Wheels.” The typical motorcycle of the day was a dirty affair, where a rider would end a ride covered in dirt and oil. Those bikes also had diamond-style frames, not great if you’re a woman in a skirt or trying to commute in a suit. Ner-A-Car touted its frame as being car-type and that body kept you clean.

Something I noticed in Ner-A-Car’s marketing was the fact that the machine was pushed heavily toward girls and women. The company said it targeted a wide age range of anyone from 9 years old to 99 years old. Marketing materials often mentioned women first as prospective buyers and noted that the step-through design wouldn’t interfere with skirts or kilts.

This was a motorcycle that you could ride while wearing your normal clothes. At the time, women had only recently gotten the right to vote in both the UK and the States, and there was a revolution of independent women, women entering into spaces normally populated by men, and women getting into sports that were then for men.

There were even a couple of famous Neracar rides. As Sports Illustrated writes, In 1921, Gwenda Hawkes rode a British Ner-A-Car 1,000 miles, traveling 190 miles a day to hit the mark. Later that year, she rode a Ner-A-Car non-stop for 300 miles.

In the image above, you can see some of the Ner-A-Car’s quirks. The handlebars lever linkages, which turn the wheel. The fender is fixed to the rest of the body. That wide fender, along with the rest of the body, is supposed to keep the rider clean, that way they don’t have to dress like a motorcyclist to ride the Ner-A-Car.

In 1922, motorcycle racer Erwin G. “Cannonball” Baker rode a Neracar from Staten Island, New York, to Los Angeles, California. It took him 27 days, 5 hours, 28 minutes to complete the 3,364-mile ride, averaging around 19.41 mph and consuming 45 gallons of fuel. In the end, the Neracar got 74.77 mpg and consumed just over 5 gallons of oil, too. The trip cost $15.70 ($284 today).

A Good Idea That Didn’t Catch On

Despite glowing reviews and casting perhaps the widest net of riders, the Ner-A-Car didn’t really catch on. In England, the Ner-A-Car evolved over the years. After the introductory model, there was the Ner-A-Car Model B with a larger 285cc engine. Then came the Model C with an even larger 350cc Blackburne four-stroke engine and a conventional three-speed manual transmission instead of the friction drive. Later variants would include a high-end Ner-A-Car with a rear swingarm and quarter-elliptic leaf springs, a bucket seat with its own suspension, a windscreen, and an instrument cluster.

None of these seemed to captivate the market and British production halted after 1926 with just 6,500 units produced.

Meanwhile, the original American Neracar saw fewer changes. The engine would be bumped up to 255cc, a second seat would be added, and additional lighting was added, as was a pair of rear brakes (none up front) and a storage box. America’s Ner-A-Car was slightly more successful, selling around 10,000 units before production ended in 1927.

In the end, the Ner-A-Car proved that you could bring car technology to motorcycles and make something pretty amazing. Reportedly, the bikes were even quite reliable. In America, the Neracar sold for $225, or about $4,070 in today’s money, so it wasn’t outrageously expensive. However, the public voted with their wallets and they just weren’t that interested. Thankfully, the concept of a car-like motorcycle didn’t die with the Ner-A-Car and today, motorcyclists who want something a tad different can find a number of car-like machines out there.

If you’re interested in the National Motorcycle Museum’s Ner-A-Car, it’s expected to roll across the Mecum Auctions block this Saturday. Bring some cash with you, though, as it’s expected to sell for between $20,000 and $24,000.

(Images: Author, unless otherwise noted.)

Support our mission of championing car culture by becoming an Official Autopian Member.

- This Word I Deleted From A Headline Sent Our Whole Staff Into A Heated Debate

- I Rode A Japanese Bullet Train For The First Time And It Was Nothing Like I Imagined

- What Brands Could Have Really Cool ‘Mascot Cars’? (You Know, Like A Weinermobile)

- Canada’s New Hot Rod Business Jet Is The Fastest Passenger Plane In The World

I’d skimmed by pictures of these in the past, but thanks for the more detailed view Mercedes.

I saw this beautiful example of the French Majestic recently. Very similar layout.

Adam, is that an all-black Neracar a few pics later?

It is indeed!

“That wide fender, along with the rest of the body, is supposed to keep the rider clean, that way they don’t have to dress like a motorcyclist to ride the Ner-A-Car.”

Yeah, because nothing would be more embarrassing than looking like a motorcyclist, heaven forbid

LOL, I giggle at the idea not wearing motorcycle gear as a selling point. I guess you’ll look nice and spiffy when you crash your Neracar?

Also the whole thinking behind it and the way it was marketed is pretty much exactly what Honda did with the Cub 30 years later, even the origin story of Neracher selling engines for bicycles first sort of lines up with Honda

The world was once more elegant.

“The Smith Motor Wheel was a gasoline-powered motor that attached to a bicycle as a third wheel.”

This was also used as a fifth wheel (but not as a fifth-wheel, as that wouldn’t make any sense) on the Smith Flyer, later known as the Briggs & Stratton Flyer, then finally as the Red Bug and Auto Red Bug:

https://1.bp.blogspot.com/-bs_EziD2Vjo/X03NjtVjD0I/AAAAAAAD31I/61qC7uKD7kMoyz2UOPSRGH8PIFwv1igfwCLcBGAsYHQ/s1600/smith-flyer-5.jpg

Fun fact: this type of transmission – sometimes called a disc-and-roller – was also used on some riding lawn mowers in the US. You would have a vertical-shaft engine driving a v-belt that spun a horizontal metal disc in the transmission; picture a really fast ICE-powered record player turntable.

There would then be a metal roller with a solid rubber tire on it, sitting vertically. This roller sat on a hexagonal axle and could slide left and right; this is how the speed was adjusted. The “gear shift” was spring loaded and could be moved into one of several notches to choose a “gear”.

There was a combined clutch and brake pedal: push the pedal in a bit and it lifted the rubber roller off the disc. Push the pedal a bit farther, and the rubber roller would contact a stationary horizontal bar; this was the brake. The hex shaft on which the rotating rubber roller rode (heh) had a sprocket on the outboard end, which was connected by a drive chain to transmit power to the rear axle.

If you wanted reverse, you pushed in the clutch and used the shift lever to move the rubber roller along its axle until it passed over the center of the disc; the roller would then spin in the opposite direction, moving you backwards. 🙂

(I had one of these in a go-kart when I was a kid.)

In other words, it’s a snowblower transmission.

Those are generally centrifugal clutch/cone transmissions I thought

Old school snowblowers (including most made today) use a friction disc and roller transmission. Simple, cheap, effective, plenty durable for the application, and much more profitable for the manufacturers.

The clutch for the transmission is typically mounted on one hand grip, and the clutch for the auger is on the other.

I love that you can pull the belly pan off a snowblower and see exactly how the transmission works. You don’t have to be a mechanical genius to understand what’s going on.

Example: I (not a mechanical genius) was able to completely rebuild the transmission in an old Toro where the previous owner had somehow managed to shear off the big pulley that interfaced with the belt.

Aaaaaaaaaaand I learned some stuff again. TY!

Awe man, I missed that when I went there Saturday. I’ll have to go back and check it out … oh wait … DANG IT!!!!

I did see the Smith add a wheel to a bicycle thing there though. That was wild. I had no idea that was the same company that now makes water heaters.

So many great bikes to see in one place, one last time. As for the Ner-A-Car, it reminds me of Dan Gurney’s Alligator motorcycles from 20 years ago.

Drivers of British roadsters know that the English treat weather protection as gratuitous frippery. I guess it is not surprising that covering the mechanical bits seemed more important than covering the passenger.

With the C1, BMW recognized that the biggest difference between car and motorcycle is rain.

Another fascinating piece of vehicular history.