Modern carmakers sure like to talk about how “sustainable” they are now. And, yes, that’s an admirable goal! It’s great to think about cars throughout their entire lifespan, from when they go from rolls of sheet steel into stamping machines at a factory, throughout their life of hauling you places and listening to all of the intimate conversations you have inside them, to eventually ending up rusting away in a junkyard before being melted down and turned into soup cans, if we’re lucky. There was one automaker that I can think of that was far, far ahead of the curve on this. They were the very first and perhaps only automaker ever to base a business model on the idea of upcycling, that is taking something already discarded and doing something new with it. What they took were entire chassis from junkyards, and then refurbished those chassis and used them as the basis to build new pickup trucks and a few SUVs. The company was Powell, and I haven’t been able to stop thinking about this company for days.

I think my interest in Powell was re-ignited when I found this post from the Petersen Museum archive that featured a number of pictures of Powell’s strange Compton, California factory that I’d never seen before. The Petersen gave me rights to use some of these photos, so I’m really excited to share them with you, because even though I’d heard or read how the business model of Powell was to comb Southern California junkyards for scrapped 1941 Plymouths, and use those chassis as the basis for their Powell Sport Wagon, which was a sort of confusing name, as it was a truck, not a station wagon. I guess a pickup is close to a wagon in the traditional, pulled-behind-a-little-kid sense of a wagon?

Look at that picture up there! You can see them pressure washing the zombie Plymouth chassis, in what looks like the first stages of refurbishment. There’s drums full of parts that could either be discards, or maybe evaluated/refurbished parts that could be installed on the chassis? They seem to be too organized for just scrap, as you can see in that big pile of A-arms there and some driveshafts behind them. But I’m just guessing.

What these pictures showed me was the meticulous process and preparation given to those junked chassis; they were completely disassembled and evaluated, with parts that didn’t meet Powell standards scrapped and replaced with service parts or other salvaged-but-good parts. Keep in mind, this is in the mid 1950s, so these chassis weren’t all that old, really, only about 16 to 18 years old. Plus, it was Southern California, so it’s not like rust was that big a deal, either. The Plymouth was a good choice, as it was known to be a robust, well-built and engineered chassis, and Chrysler sold over 500,000 of them in 1941, so supplies should have been plentiful.

Let’s just pause a second and think about this some more, because I think it’s worth it. Just imagine if an up-and-coming, lower-volume truck maker like Rivian or Canoo made an announcement that from now on they’re going to be building all their new EV trucks by buying all the junked 2007 Ford Crown Victorias they could find and using those chassis, after refurbishment. Everyone would lose their lettuce, but if you actually stop and think about it, it makes a hell of a lot of sense, especially if your goal is to make an affordable truck, which is precisely what Powell’s main goal was.

Channing and Hayward Powell, the Powell brothers, wanted to build what they said would be “America’s 1st car produced to sell below $1000,” and looking at ads of the era, they seemed to have pulled it off:

In today’s money, $998.87 equates to about $11,140.45, and for comparison, the average price of a pickup truck in America today is almost $60,000, so, yeah, I’d say the Powell Bros succeeded. Aside from starting with a salvaged chassis, Powells were designed with so many other cost-cutting measures in mind. Body panels were designed to have no compound curves (save for the roof) so no complex stamping machines were needed. Basic materials like diamond-plate steel were used for some panels, like the rear and the tailgate, early production bumpers were just planks of wood, and the bench seat was just foam, no decadent and expensive springs inside there. What are you, royalty, that you need your ass suspended on springs?

The front end was fiberglass, made by a nearby boat maker, and the instrument clusters seem to have been just whatever Plymouth salvage or service parts were cheap and available. I say this because on most pictures of Powells I’ve seen, they vary pretty wildly. Nothing was custom-made, if it could be helped. Grille chrome trim strips were actually door trim from a Ford. All the glass was flat, and the engines that made it all go were also salvaged and completely re-built inline-sixes from Plymouth (usually) as well.

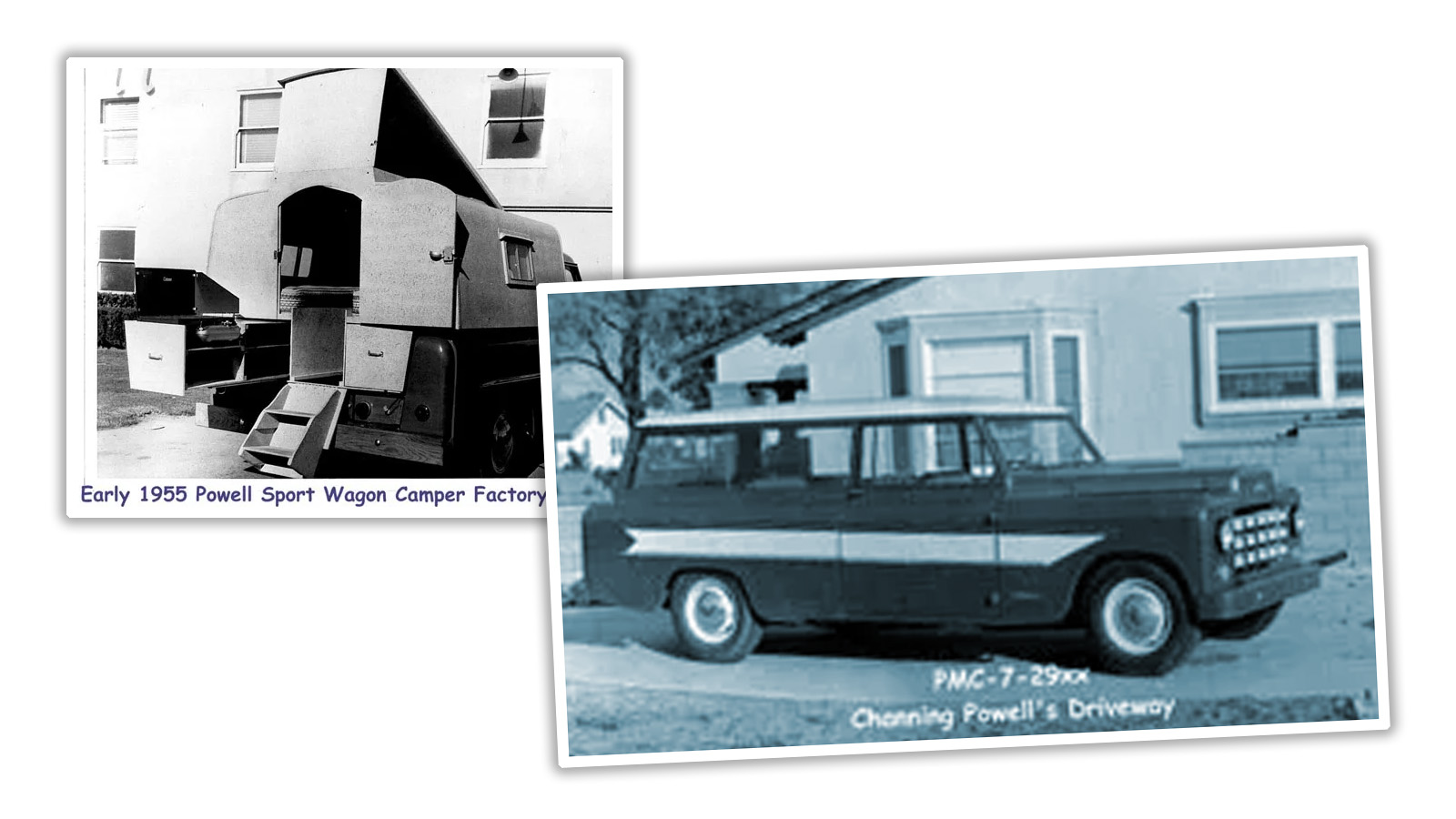

I spoke with the curator of the Petersen Museum, Leslie Kendall, and he described the Powell factory as being an assembly line of sorts, but one that moved at a tempo of a truck going from one “station” to another at a pace measured in days instead of the usual minutes. Still, despite the leisurely rate, about 1,170 Powell Sport Wagons were built, with most being trucks, but about 200 were Wagoneer-like enclosed SUVs, and there was even a prototype camper built, with all kinds of flaps and swing-out and up sections:

What Powell Sport Wagons were best known for, I think, was an optional feature they had: tubes. Specifically, in the bedsides of the truck, you could specify one or two long, cylindrical drawers where you could store fishing poles or rifles or javelins or six-foot party subs or whatever long, narrow things you needed to carry. In our current era of under-bed storage lockers and inside-tailgate storage and all kinds of clever hidden truck compartments, Powell can be seen as a real pioneer.

In this photo you can clearly see that the rear is made up of no-skid diamond plate steel, and you can see the tube-like drawer extended; this truck only had one specified. Also interesting is the spare wheel compartment under the bed, accessible by removing that rectangular panel.

There’s around 109 surviving Powells , and while they’re not terribly well-known even among gearheads, I think they’re due for some newfound relevance. As really the only true example of automotive recycling on a significant scale, I feel like there’s lessons to be learned here, especially in our upcoming era of skateboard-chassis’d electric cars. Will there be a neo-Powell in 2055 that takes Tesla skateboards from the 2030s and 2040s, slaps in new batteries and a rugged, simple pickup truck body, and sells it for dirt cheap? Probably not, but a boy can dream.

Jason, you should revisit your other article on how expensive it is to repair a slightly damaged Rivian or other EV.

Well lets say someone did get a fleet of Crown Vics to rebuild and modernize as something else. The price would have to be significantly lower than a new car or even a CPO and I don’t see that happening. So the time for this type of repurposing is over except for really desirable classic cars.

Great way to reduce wastefulness!

There is a company in Poland with somewhat similiar working principles, but for totally other reasons, and costs. It is “Defender Factory” that sells fully refurbished Land Rovers, using donor cars mainly for VIN number, so there is no need to be compliant with today’s emission and safety regulations for new cars.

Here is their website in polish: https://lr.pl/defender-factory/o-defender-factory

And about company in english: https://forum.lr.pl/defender-factory-en

Most important in parts from their description:

We do not replace parts; we assemble a new car from scratch, just as in a factory. In older models, one usually needs to start with a new, galvanised frame.

We assemble a new car from new or reconditioned components (often old but good, better than new ones from current production). The “donor” gives us the VIN and registration certificate. They get a new car, only with the difference that the car’s registration document contains the year of manufacture of the “donor” car.

Models 90 and 110 (regardless of the body version) cost EUR 59,000 net. 130-inch models cost EUR 69,000 net. This applies to cars with diesel engines. Original models with V8 petrol engines (and we only work with originals) can be a lot more expensive, it depends on acquiring the right, original “donor”.

the average price of a pickup truck in America today is almost $60,000,

Seriously? I think I knew this but it’s still shocking. That’s $5,000 in 1955 dollars and the median income was $4,400. Today the median income is around $67k meanwhile in 1955 the Ford F100 started at $1,460.. I have no idea what I’m trying so say, but there it is.

It seems to me these were work trucks, take a look at white work trucks in your area and you will see them outfitted with large open tubes or capped off PVC, these are for pipes, spirit levels, or various other work related items. So the tubes plus the no nonsense styling and creature comforts tells me the target audience was really plumbers, tradesmen, construction workers etc.

Safety and emissions laws would make this hard to do today. Still very cool idea!

Yeah safety would be difficult, but I’m sure there are plenty of emissions-compliant crate engines out there that could be swapped in without too much trouble. Even with EVs, one could probably rig up a simple range extender generator and convert worn-out EVs into cheap hybrids!

I could see a cottage industry of stuffing little generator engines in the frunks of worn-out Teslas and F-150 Lightnings and such… cheaper than replacing a battery, and even if the engine isn’t powerful enough for sustained driving, it’d let you recharge anywhere you can get fuel.

I dunno, some manufacturers have gotten away with glider chassis for semi trucks. This way, they can skirt EPA restrictions: https://www.fitzgeraldgliderkits.com/what-is-a-glider-kit/

the styling kind of predated the eventual normal of trucks, I see a lot of Studebaker Champ in that design. That being said, imagine if they had gotten a hold of a bunch of military surplus deuce and a halves and transplanted the Hercules JXD engine instead, maybe even pulled the 6.6 to 1 t case and started the true offroader experience before or maybe at the same time GM contracted Napco to do it for them.

Love the idea but…

I hate to put a damper on it, but the biggest problem can be summed up in two words “labor intensive”.

In the 1950’s There were lots of mostly men looking for work after World War II. Manufacturing was labor intensive and done widely across the country.

Today it would be very hard to find cheap enough labor. People are needed to do the teardown of the old cars and the rebuild of the new cars that essentially has to be done entirely by hand. Unfortunately nearly all manufacturing these days is done with computer-aided design and robots with the business executives not wanting to hire huge numbers of workers.

Wait a minute…if this was a real thing and could pay men and women a decent middle class wage with benefits, this could turn around a decades long problem of erosion of the non-college educated middle class…

Unfortunately, not likely in this country.

I mean, to be honest the Lordstown endurance looks an awfully lot like a 5 year old Chevy truck was pulled from the junk yard tarted up with a grill and the gas V8 transplanted with a battery and electric motor.

Considering the EV craze being pushed down everyone’s throat, the fact that some of these at this point fairly well established electric conversion places has not started simply pulling decent cars with blown motors from the scrap yard and converting them to sell, just solidifies your thought about potential profit not being there.

I would happily drive let’s say an 1980’s bi-turbo Maserati if it had either the magna motor axle or even a tesla swap kit in the engine bay….but if the price was over 20K it might be hard to finance or justify unless it had 3 year warranty at the very least.

I’m just disappointed one of them isn’t named Herb

Hat tip!