There were plenty of column inches written on the Tesla Cybertruck and its adoption of 48-volt technology; or at least, there would have been, if anyone read magazines or newspapers anymore. Regardless, it was a headline part of the truck—that 12 volt electronics were a thing of the past, and 48 volts was the future. Now that these trucks are out in the wild, we can see the truth of the matter. Yes, the Cybertruck is a standard-bearer for 48-volt technology, but it’s still firmly got roots in the 12-volt world, too.

The teardown experts at Munro & Associates have been steadily dismantling the Cybertruck, and now they’re sharing insights into the electronic side of things. For this latest video, we’re getting the lowdown from Tom Prucha, director of electrification at Munro & Associates. He’s joined by Dale Cook of 3IS Inc, a company that specializes in benchmarking automotive electronic systems. Meanwhile, over at Autoline Network, they’ve been covering the work of Caresoft—another company in the automotive engineering and benchmarking space. The video interview with company president Terry Woychowski sheds plenty of light on the Cybertruck’s electrical architecture.

Between all these intelligent minds, we can learn a lot about the benefits of Tesla’s 48-volt technology. At the same time, we also learn why there is still so much lower-voltage technology lurking within.

Munro Live has shared a wide-ranging talk on the 48-volt technology.

What’s The Point Of A 48 Volt System?

Let’s first mention the typical automotive wiring system, which runs at 12 volts. Basically, you have a battery under your hood (or in some cases in the trunk) that supplies nominally 12 volts to power up the car’s various control modules, and to kick over the starter motor to start the internal combustion engine. With the engine running, the alternator provides the nominal 12 volts to charge the battery and run all the car’s accessories and modules. The 12 volt system runs just about everything—from the engine control unit, to the body control modules, to the power windows, locks, dashboard, headlights, and everything else.

Naturally, then, there are a ton of wires carrying 12 volt power to everything in the vehicle. That’s a lot of copper—often many miles of it, in fact. Copper doesn’t come cheap, either, so if you could reduce the amount of copper you needed, there would be some serious cost and weight savings on the table.

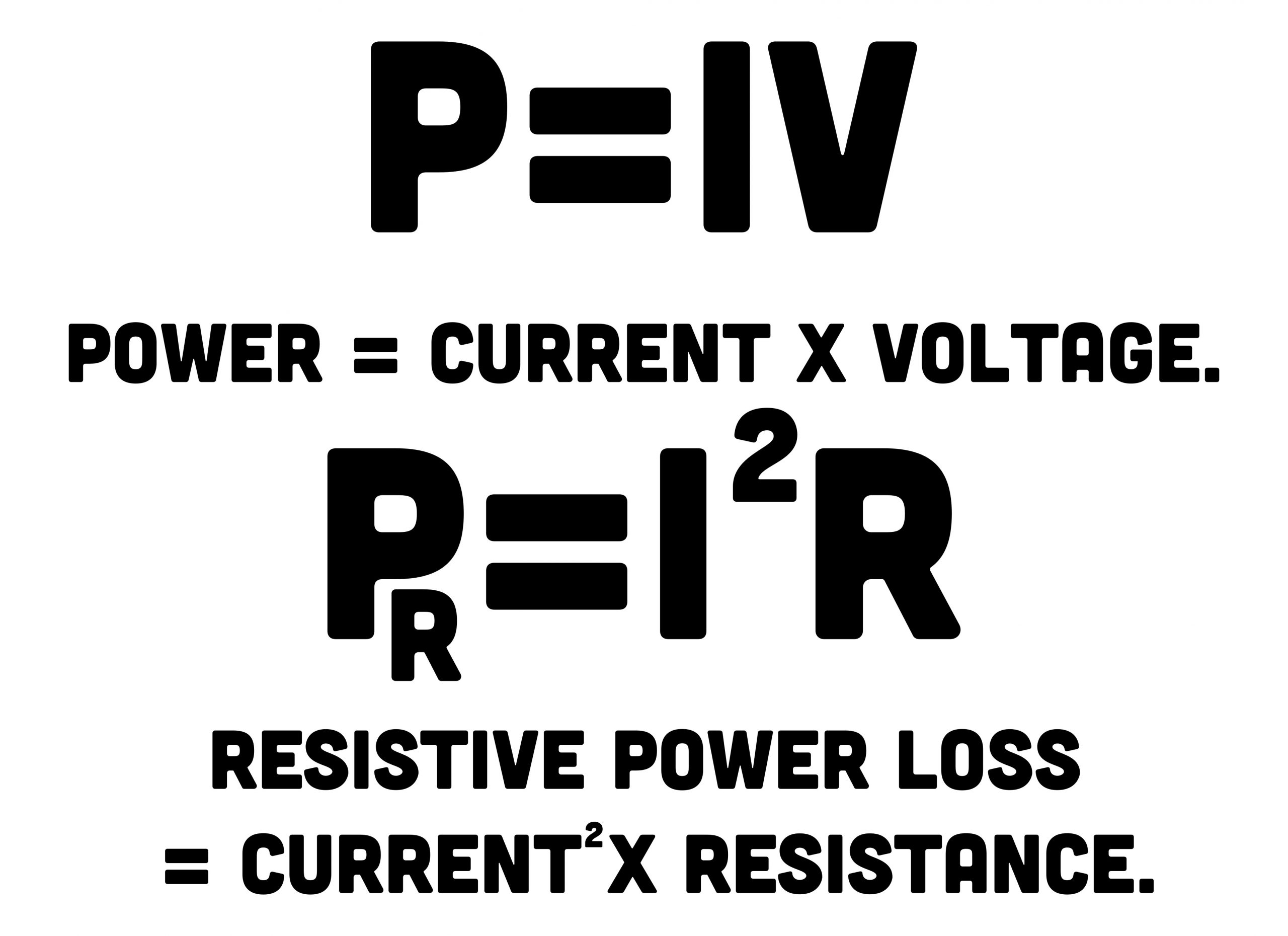

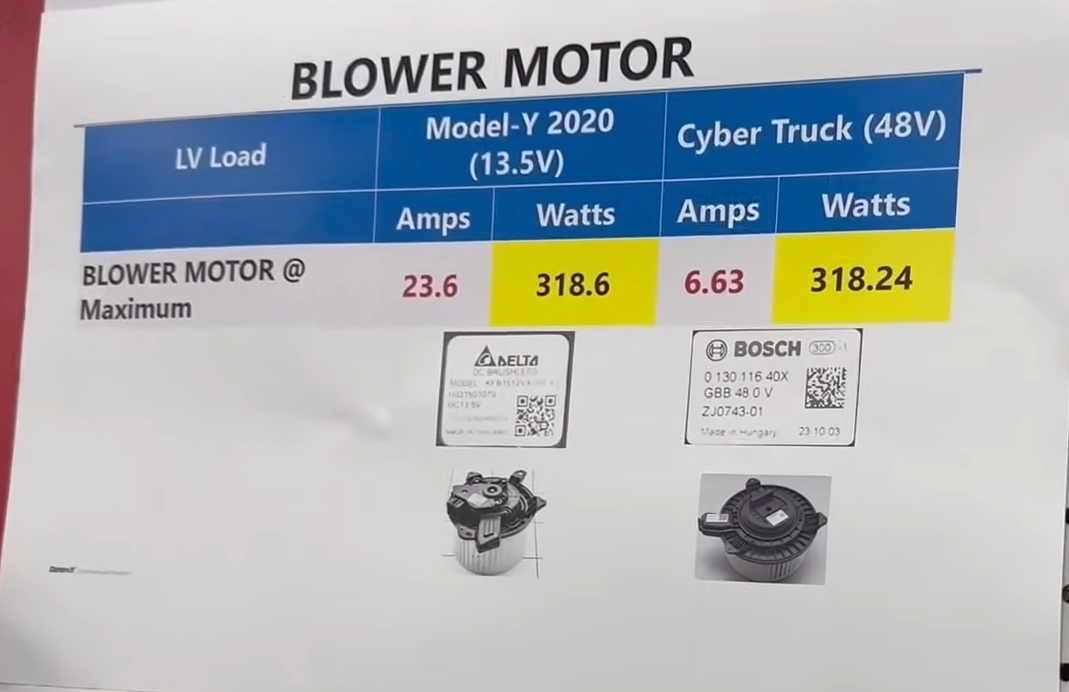

Switching to 48-volt accessories has long been a dream of many an automotive engineer [Ed Note: 48V was happening well before Tesla, but not nearly to this extent. -DT]. That’s because with higher voltage, one can get the same power with a lot less current. That’s because power equals current multiplied by voltage. If you double the voltage, you can get the same power with half the current, and so on.

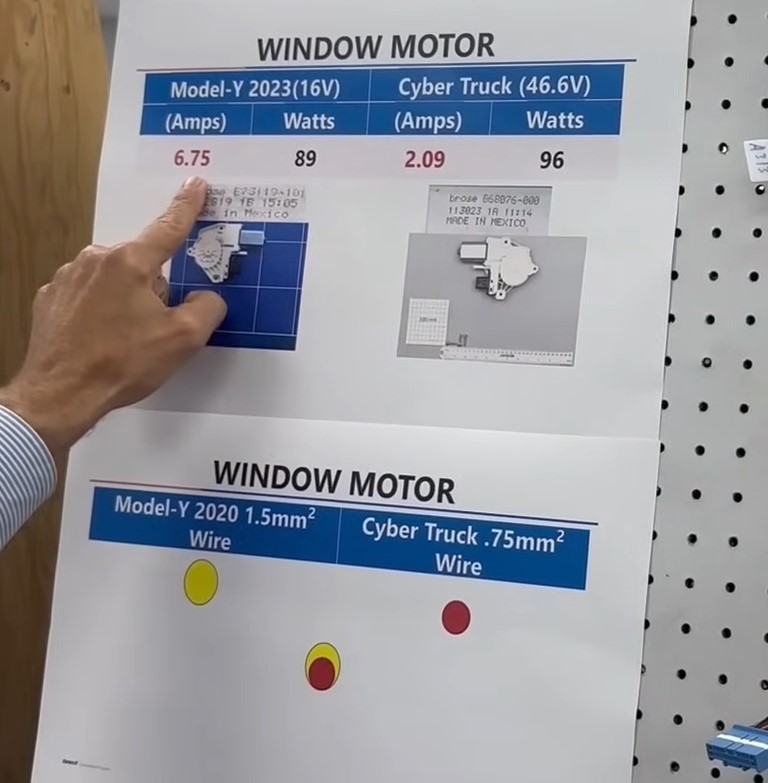

Reducing current for the same power level is desirable—this is because resistive losses in a wire are equal to resistance times current squared. If you slash your current, you slash your resistive losses significantly – losses that would otherwise become heat. This allows you to run thinner wires to deliver the same amount of power. You thus save a ton of copper, which is pricy and heavy, and all your accessories use less power, which is good for increasing range in an EV.

At the same time, switching to 48-volt systems comes with challenges. If you wanted to go to a purely 48-volt architecture, you’d have to replace virtually every last motor and bulb in the vehicle with bespoke parts, even down to things like the radio. And a whole lot of switches, too! As more vehicles start including 48-volt components, this becomes less difficult, but even today, a lot of automotive running gear exists in 12-volt form only. By and large, any automaker that wants 48 volt parts has to design them from scratch, or pay a supplier to develop them.

Tesla has actually been inching towards this for some time. Some of the company’s earlier models adopted a 15- or 16-volt system, such as the Model S Plaid. Various different people refer to it by a different nominal voltage, but basically, it’s just a touch higher than a typical 12-volt automotive system. To be clearest, the Cybertruck uses some 48-volt parts, and some parts that run at the lower 16-volt level as per the company’s older vehicles. The difference between 12 volts and 16 volts is pretty minor—some components could conceivably run at either 12 or 16 volts without major modification. However, 48 volts is a high enough jump that it requires specifically-designed parts.

Caresoft shared its findings back in July, giving us a close look at the components and analyzing the differences between the 16-volt Model Y and the 48-volt Cybertruck.

A Look At Tesla’s 48 Volt Hardware

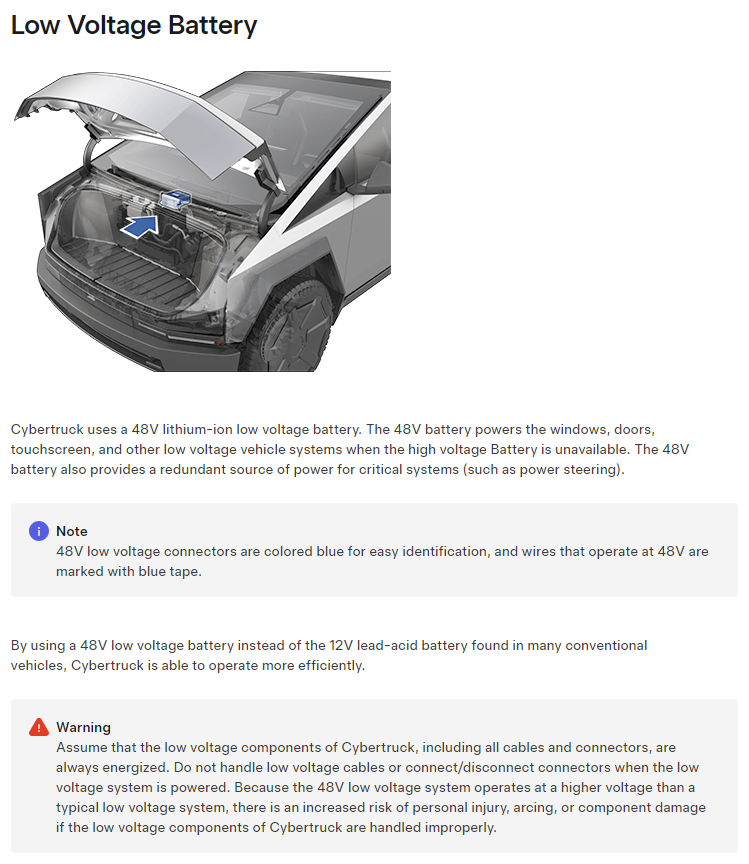

Tesla has gone out of its way to make 48-volt technology obvious, distinguishing it from other wiring in the Cybertruck. “Any connector that has 48 volts in it, they’ve gone with either the baby blue housing or shroud for the connector, or they’ll put a baby blue piece of tape on the connector to tell you that that’s 48 volts,” says Cook.

Why the visual distinction? It’s useful to know what you’re dealing with when you’re working on the vehicle. “It’s not harmful, it’s in that semi-safe zone, but, eh… you don’t wanna touch it,” says Cook. “It can hit you in the back of the elbow a little bit, so to speak.”

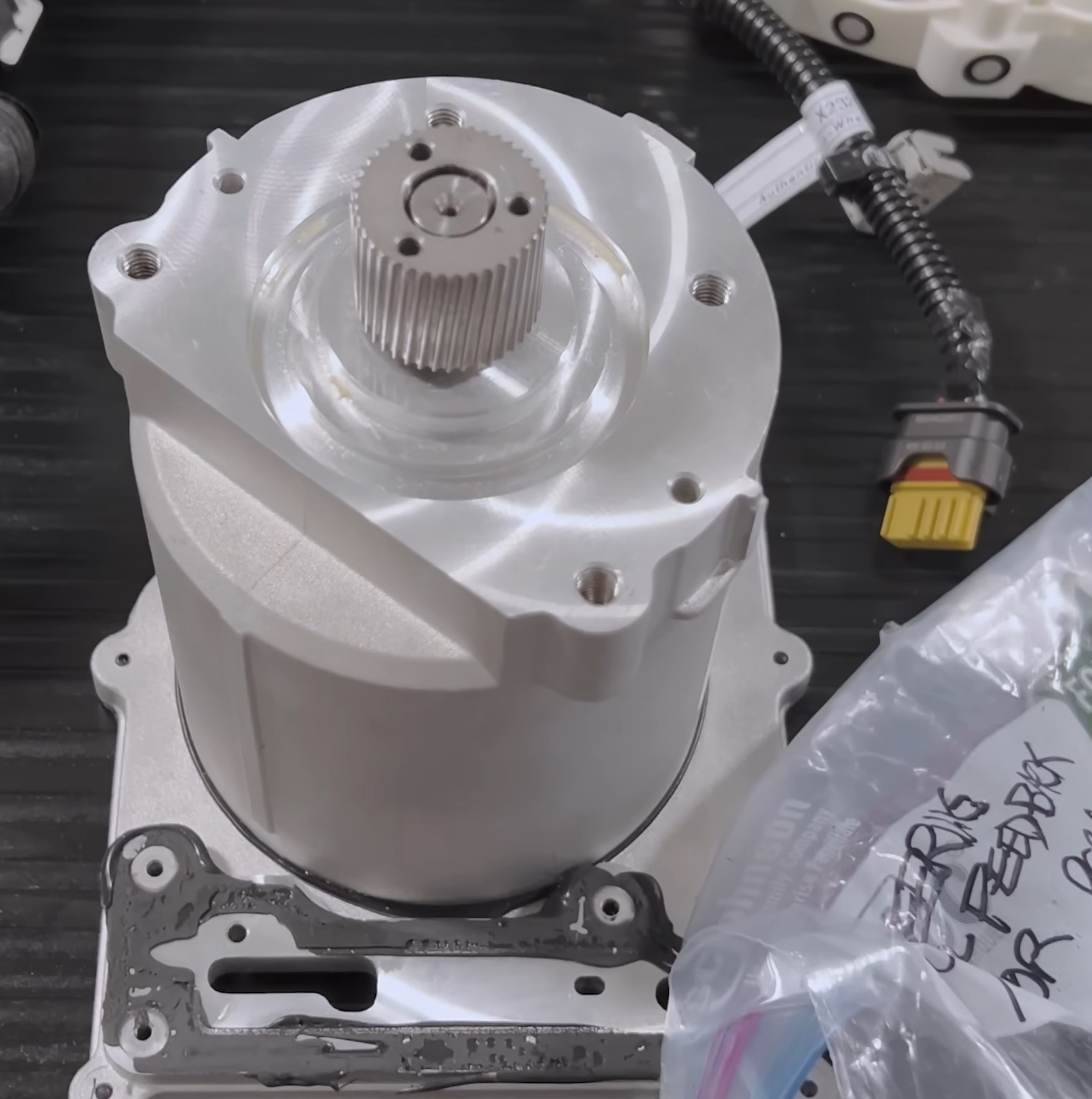

When it comes to 48-volt systems, Tesla did a lot of work, but it didn’t do everything. “What Tesla did with 48 volts is they took a lot of their big loads, the radiator fans, the cooling fans, the power steering motors…” Cook explains. “We say it’s a 48 volt system, but there’s still 12 volt components on the car.” Indeed, if you look at the work done at Caresoft, they prepared lists of which components are 48-volt, and which run at the lower voltage level. Most parts with high current draws—headlights, pumps, the radiator fan, the steer-by-wire system—all got designed for 48-volt operation. Meanwhile, things like door lights, interior lamps, and the radio all operate on the lower 16-volt system.

“You’ve still got some historical modules that Tesla didn’t do the investment to convert them to 48 volts, ” Cook explains. Why? Time and money to do the engineering are the likely reasons—he notes that suppliers want to be paid to develop bespoke 48-volt components where none currently exist. Meanwhile, on Tesla’s side, there needed to be a business case to justify the expenditure on that R&D—either internally or at suppliers. “That could be anything from you know, reducing material costs through less copper… and then it could also be efficiency which would play into how often does this thing get used,” Prucha posits. He notes that for a seat adjustment motor, for example, there’s very little reason to improve efficiency by making them 48-volt given that they’re barely ever used. And thus, Cook notes that they’re still running at the lower voltage—likely commodity parts already seen in other conventional models.

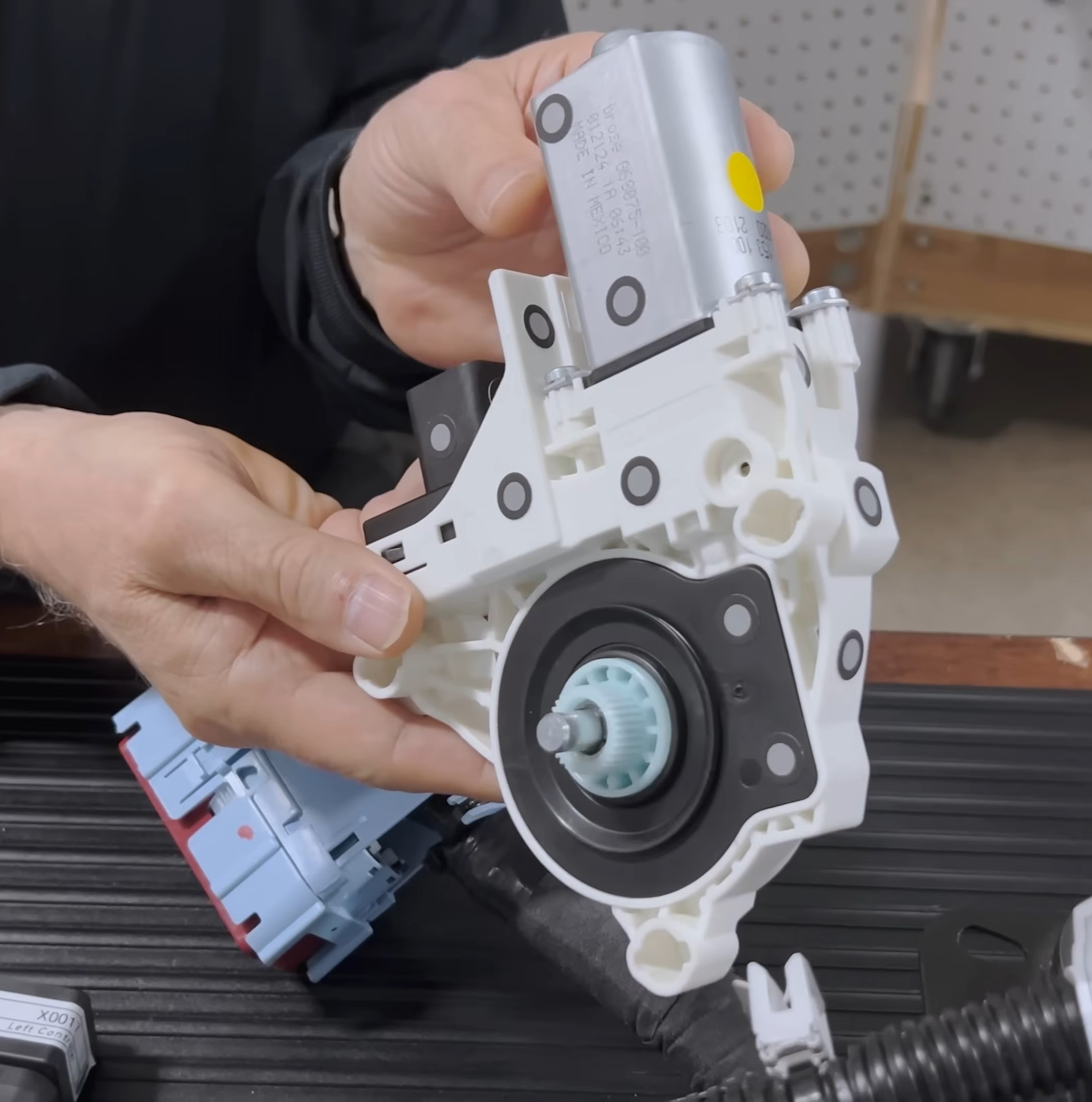

Still, some of the smaller bits and pieces did get converted—like the power window motors. “They’ve got a supplier, Brose… they redesigned the motor to operate off of 48 volts,” Cook explains. He notes that the part is still a simple brushed DC motor; it’s just been wound to suit 48-volt operation instead.

The switch to 48-volt power is most relevant for devices like the steering motors which are both higher power and used more often. “The steering is an obvious one, because you go from… instead of a 4-gauge wire feeding power, you’re down to an 8-gauge, or it may even be a 10 gauge,” says Cook. Higher-numbered wire gauges refer to wires that are smaller in diameter. “Your diameter of wire is reduced, the amount of copper is reduced, and you end up with a fundamentally more efficient system because I’m not running heavy copper everywhere,” says Cook. “I am a firm believer, if I can take weight out of the copper, it’s a good thing.” He notes that compared to 16-volt or 12-volt systems, the current is slashed to a third or a quarter, respectively.

Just as not everything runs off 12 volts, not everything can run off 48 volts either. Obviously, the traction motors run off the high-voltage battery at 800 volts. Similarly, Cook says the air conditioning compressor is running off the traction battery, not the 48-volt subsystem. He notes it simply draws too much power to feasibly run it off the 48 volt system. In any case, it’s much the same in ICE-powered vehicles—AC compressors draw a lot of power, in the multiple kilowatt range—that’s why they’re traditionally driven straight off the engine.

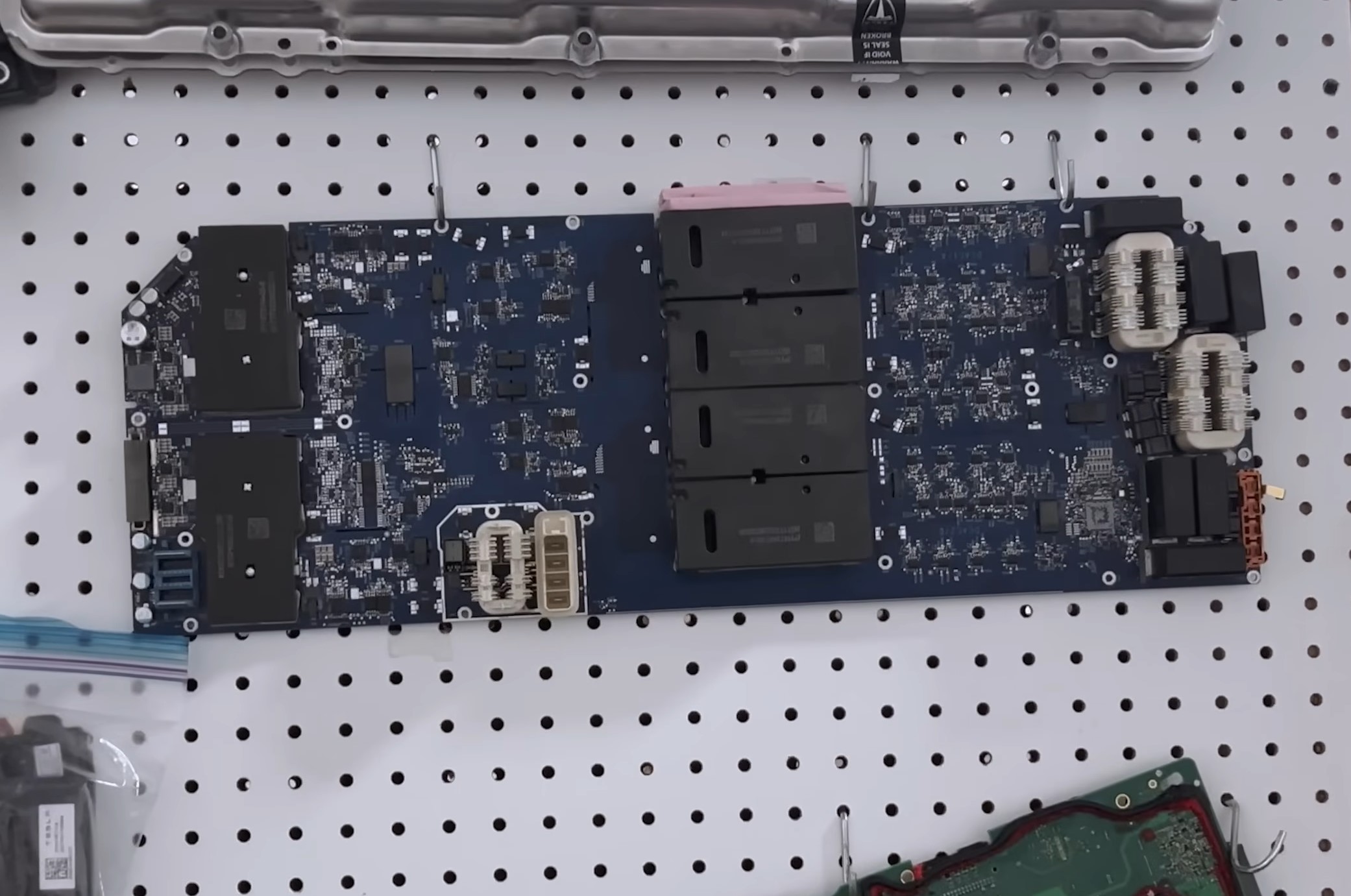

The body control modules are what runs the show, and these parts have to handle both voltages in the vehicle. “These are the two main front controllers, there’s a left and right, this circuitry here is basically a switching circuit that can convert 16 volts to 48 volts and its bi-directional.” says Cook. “It can put power towards charging the battery, or towards the vehicle, whichever way it wants to run.” The left module is also charged with handling jump starts if the Cybertruck’s 48-volt auxiliary battery is dead. “The left controller has the jump start post that comes into it, and the jump start post is isolated from the battery,” Cook explains. “If you connect up to jump, it figures out what voltage you’re using, you can use 12, 16, or 48… this will create the 48 volts from that input and wake up the rest of the car.”

Where many EVs still rely on 12-volt batteries for standby power and to energize their main battery contactors, the Cybertruck uses a compact 48-volt part instead. “We’ve seen lithium ion batteries as low-voltage batteries before, but it’s the first time we’ve seen one in 48 volts, and it’s really small.” says Prucha. And yet, it’s actually got quite a lot of capacity. “It has quite a bit more watt-hours than the 12-volt one that this replaced,” he says, without being specific as to how much.

The connector for the battery is a unique part, designed specifically for this application. “There’s communication in this center portion, and you’ve got the positive and negative terminal for the battery.” He notes that just placing the connector down and locking the first latch isn’t enough to energize the system. “The battery is still off, it’s not sending power down the wire,” he says. “You have to lock the connector position assurance, in the industry we call it a CPA,” Cook says, denoting a red sliding latch that positively locks the connector in place. “For Tesla we’ve kinda coined it’s an ECPA,” says Cook, without explaining the acronym. Perhaps he means Extended, because it comes with a neat bit of extra functionality. “It has a little shorting bar in here that makes a connection and tells the battery it is connected correctly to the vehicle,” he says.“If somebody wants to shut their Cybertruck down, you go to the center screen, you select power down… you [then] go to this battery, you release the CPA, and the car is dead,” says Cook. Without the 48-volt battery connected, the high-voltage battery’s contactors are deenergized, and the whole vehicle is basically switched off. It’s basically a “poor man’s kill switch” assuming you’re comfortably able to reach the 48-volt battery. It’s useful for both storage purposes, and for powering everything down when doing repairs to the truck. Only thing is, it’s kinda tucked away.

Noting his past work in the industry, Prucha explains that earlier efforts to go to 42-volt systems failed because not enough suppliers developed parts to run at that voltage. However, Cook also notes the state of technology at the time, which largely relied on old-school relays for switching. They’re basically magnetically-activated switches, which get quite bulky when you want to use them at 48 volts instead of 12 volts as greater isolation distances are required. However, Cook notes there are now readily available automotive-grade semiconductor parts to do the job instead, which didn’t exist decades ago. They’re much smaller and more compact, doing the same job as a relay in a more compact form. “Now for this module, there are 48-volt drivers, 48-volt motor drivers… you can look up the part and buy them off the shelf.” says Cook.

Will 48V Become The New Standard?

Cook also highlights the PCS2—the power conversion module. “That does the AC to DC, it’s a dual 48-volt, it has the capability of bringing… the charge port comes in and it can do whatever conversion is necessary to charge the batteries.” “It is state of the art… it uses planar transformers, [which are] really thin…” says Cook. “Fundamentally, you’ve got the ferrite cores and the circuit board are the windings of the transformers. He believes the tech may have trickled down from another Musk company. “It’s really advanced technology,” he says. “This may have been something, and I’m speculating, that came down from SpaceX to the car company, because this is the type of thing… it’s rocket science.” The company’s tear down work has involved documenting the exact operation of the device, down to the bare metal level. If you’re an electronic engineer at a competing car company, you might pay big money to get access to that report—which is the business these people are in.

The problem with 48-volts is that it’s not yet an automotive standard. If you’re interacting with other stuff, you need 12-volt capability. That’s why the Cybertruck can jump off a 12-volt battery, and also why it has a special trailer controller module. Rather than use a separate 12-volt battery and electrical system, Tesla just decided to use DC-DC converters to step voltages up and down where needed. A great example is in the trailer module. “The trailer runs off 12 volts… the lights are all 12-volt bulbs or 12 volt LEDs, you’ve got a 12-volt system so you need to create that voltage,” Cook explains. “A whole separate module was created just to manage that 4-pin and 7-pin connector for your trailers.” Sadly we don’t get a look at the actual module, but it’s basically just a bunch of power converters and control logic in a box.

Will 48 volts stick around as a new standard? “It gives you the opportunity to save some copper,” says Cook. “When all’s said and done, weight is king when you talk about an electric vehicle.” The benefit is that systems run cooler, too, since they draw less current. Prucha also notes that the great number of mild hybrids out there have 48 and 12 volt systems, and they could similarly be pushing towards the adoption of the higher-voltage standard, too.

While Tesla didn’t convert the whole truck over, the engineers admit there’s good reason for that. “We know that there was no real practical way to convert everything that was 12/16 volts to 48, but they seemed to take a somewhat intelligent approach to which ones they did convert,” says Prucha. Cook notes that he thinks Tesla did a good job at prioritizing components worth converting, while ignoring others that didn’t offer “bang for buck.”

Ultimately, expect to see more automakers head this way in future. Just as 12-volt tech blew 6-volt wiring out of the water in the 20th century, 48-volt hardware could become the norm. The more automakers adopt the technology, the easier it will become to implement in the future.

Image credits: Autoline Network via YouTube screenshot, Munro Live via YouTube screenshot, Tesla, Bentley, Summit Racing, Supercheap Auto

As the six volt cars aged into the twelve volt world, some were retrofitted with a dual voltage system. The genny was replaced or rewound to put out twelve volts, the voltage regulator and battery were replaced as well. Most of the high draw items like the starter, ignition, and headlights were fed twelve volts, while components under the dash got six volts from a tap in the battery. Six volt headlights were already hard to come by in the sixties, and for a tired oil burning engine, the faster crank and hotter spark made a difference. Done right they worked well enough but they gained a reputation as a kludge to get a few more years out of a bad electrical system.

Interesting that modern cars have starting using this concept again, but for different reasons. This time with parts from a space ship, instead of JC Whitney!

Admission of ignorance: How does one jump an electric car? If the battery is dead, and it’s the sole source of power, it’s not like you’re kick starting a power plant, there’s nothing there to start. Nothing to generate power to actually run the vehicle. What is being jump started? How does it get you down the road to get another battery… or alternator… or whatever?

So, there’s two batteries in the vast majority of EVs – a low voltage (12, 16, or 48 volt) one, and a high voltage (typically “400” or “800” volt) one.

The low voltage one runs the computers and accessories, the high voltage one runs the motors and the AC and often the heat. The high voltage one is charged from an outlet, the low voltage one is charged from the high voltage one.

So, if the high voltage one is dead, but the low voltage isn’t, you plug the car in to the wall, a generator, a sufficiently high-powered battery-based power station, or a public charging station.

If the low voltage one is dead, but the high voltage isn’t, you jump start it just like you would an ICE car, the computers boot up, enable the high voltage battery, and then it can power its own low voltage system.

If both are dead, you jump start it (because it won’t charge the high voltage battery until the computers are running), and with the jumper cables still in place, you plug it in so the high voltage can charge (and also charge the low voltage system).

Excellent article, as a wire harness engineer I appreciate the deep dive on this. There are a set of regulations and testing that needs to happen for this 48V architecture to be used with more suppliers and OEMs. As you noticed, the majority of the components that are capable of 48V are in-house made by Tesla, not suppliers. There are better ways to save weight from a cooper perspective, redesigning your vehicle electrical architecture will accomplish that (There is an article somewhere about Ford Mach-E heavy usage of wiring because of a bad design from an architecture perspective).

Surely these reduced costs will be passed on to the consumer.

In a way they definitely are, for increased mileage due to lower weight. They cut upwards of 200lb out of the electrical system and wiring harness by using 48v.

So when Musk was crowing about the 48-volt electrical system and sending binders to other car companies’ CEOs telling them how to do it properly, he left out that the CyberTruck has still got a 12-volt system just like every other 48-volt vehicle on the road that preceded the CyberTruck.

Also forgot to tell that his harness is in serie. What a joke.

Time to reiterate for the 50th time, that short of actuation motors, which generally can run at quite a wide range of voltages assuming proper current and thermal control (the exact same ebike motors are used for everything between 24 and 72V nominal atm for example)…. almost 0 electronics actually run at any of the voltages they are fed, and instead down convert to some other value, either on an on board controller or buck converter or inverter or step-down (or realistically some combination of the 2).

Anything with an microprocessor is almost certainly being fed with less than 2V (and these days that includes basically everything). That 12-18V (realistically) electronics system already includes stepdowns at basically every single end component.

What I am saying is that the common “it needs a bespoke part” line I see on this website suggests it isn’t honestly an absolutely trivial engineering change that costs dramatically less than 1 dollar in changed electronics parts. Or that you couldn’t go the PC route and have a local step-down module that intakes 48V then distributes your 12V or whatever power through the rest of the region in the car so that you can save the tiny amount of engineering work to change the individual components.

Tesla does this, obviously, in some cases. End of the day the complexity in wiring and cost in cabling is dramatically higher than even adding 6 or 10 48-12V modules throughout the car, as half-assed of a solution as that might be.

We need to stop being so impressed, and just start being annoyed at the laziness of legacy manufacturing. Your phone charger delivers (depending on situation) 5V or 9V or 12V or 20V or sometimes higher DC starting from a 120V or higher AC source. Your phone accepts it, despite being either a 3.7 or a 7.4 (dual cell) battery. It’s SoCs generally use less than 1V, but many of the individual subcomponents have their own voltage regulation circuitry as well.

Somewhat hyperbolic, grossly oversimplifyed but true, your grandparents radios were designed adhoc from anything between 1V and 250V…. the same radios could be hooked up to DC mains, AC mains or powered by batteries with effectively identical circuitry and components. They were sold as universal radios. They had run on 1.5 or 6V DC batteries, 7.5V, 22 all the way up to 90V or even 300V B batteries. Early color vacuum tube TV sometimes had to step up their input to 900V or above!

This is not something to be impressed with. It one of the many regimes that most automakers are quite a bit behind the times. There are… reasons… why 12V has stuck around for so long, but the biggest has always been sheer inertia. Why bother fixing what’s only moderately annoying? Why have safe headlights and amber tail lights when you can lobby governments to keep restrictive and cheap regulations in place that harm the general public?

Even though I generally agree with you, I think you’re greatly minimizing the “bespoke vs off the shelf” difference. It doesn’t matter if only a tiny engineering change would be needed: you still need an engineer to design that change and a supplier to validate, test, and produce a special run of parts just for you with that tiny little change. That takes time and money compared to just buying the same old window motor you’ve been buying for decades!

I mean… yes. but lets be real in terms of amortizing that change is really nothing in the long-run. And changes happen pretty regularly regardless. That supplier might have been bought out, they may have started using a different subcomponent because of IC supply chain issues…. ETC ETC.

No it isn’t nothing, but it isn’t something to be ‘lauded’ as this huge shift.

If your new part doesn’t sell, there is no long run to spread the expense over.

Suppliers are simply waiting until they know they have enough future sales to cover the cost. Without future sales, today’s one-off rates are quite high.

Auto makers have been avoiding the change because each individual car and truck project only gets a very small improvement from the changeover. Because every car or truck model is considered an independent project with its own limited budget, there’s no money to make these changes.

GM or Ford could have done this with a company-wide mandate that certain subsystems must be 48 volts going forward, but without suppliers on board first, it’s an expensive proposition that they each wanted the other company to bear.

Inertia in other words. But yes. The key is automakers could have setup their own interim solutions that allowed the subsystems to see 12V, but have 48V (or similar) distributed instead. Using local downconversion modules in doors and front/rear panels. It would have been “hacky” but still likely cheaper even once you do a run for a single vehicle (given the wiring cost reduction).

And then take that benefit each step of the way while they get the suppliers on board. Even in Teslas “swap” they do this in in more than a few spots. A component that can likely be removed in future minor updates. But yes, why bother being a first mover when everyone uses the same suppliers anyways, and you can always just lag behind and not invest even the minimal amount of effort in development yourself.

That is the actual attitude, and sure, it makes short term financial sense. But it’s also directly the reason why they are so far behind in key areas.

It still would cost less than thr new molds, wiring, and design for headlights/taillights that every single car every single refresh gets.

Yeah, it’s inertia, but it’s also the budgeting method the traditional automakers have used for new models and model refreshes.

If the leadership of any one of the world’s large automakers had demanded and budgeted for the electrical system as a common component across their entire product line, the change would have come decades ago.

It wouldn’t have even been very difficult, but I don’t think anyone influential outside the engineering departments was sold on the cost/benefit analysis of making the change until now.

I think this is where Elon Musk is more effective than the average CEO. He listens to the engineers. Then he publicly promises much of what they say is possible, and follows up with intense pressure to get their loftiest goals done cheaply. It seems he’s always betting the company on his ability to get the engineers and production workers to work overtime.

It’s not a company I would work for, but it’s been effective so far.

Higher voltage cars have great potential.

So, is the 48V minus side tied to the chassis?

More specifically is the 48V minus side of a cybertruck tied to the chassis?

What about the 12V system? Is that left floating or is the minus side tied to the chassis?

ISO 21780 2020 “Road vehicles — Supply voltage of 48 V — Electrical requirements and tests” seems to indicate that the grounds are common:

There is quite a bit of concern about data connections between 12V and 48V systems and 48V systems losing their ground.

Sorry, there are better ways to criticize Elon than this comment’s original content. – ED

I’d say a discussion around 48V vehicle architecture is worthwhile though, as it has benefits for all cars, not just Teslas or EVs. This is like the jump from 6V to 12V in cars, and the CT isn’t the only player in this space today, and others will be jumping on board.

It’s an interesting article about engineering decisions that were made here and why.

I’m no fan of Elon, or that monstrosity of a “truck”, but we’d be doing ourselves all a disservice ignoring the innovations.

Also, you could keep your unpleasant and disgusting words to yourself. Maybe just don’t click the article, AND feel the need to chime in? No one will miss you, I promise.

One problem I can foresee is that thinner gauge wires are far more susceptible to breakage due to crimping, abrasion and rodents.

48V will in some cases do a better job of keeping rodents away though. 12V in your mouth is tingly. 48 hurts. Only applies when the lines are hot, but it’s something.

Personal experience?

Actually, never hit 48 exactly. Plenty of 9 & 12 on the tongue as a kid. 110AC a couple times, plus a couple cattle prods (8000? But no current)

Yup.

Mice are eating the insulation and damage to the copper is incidental.

I believe his point was that thicker copper (vs thinner for increased voltages) would better stand up to stress, whether or not the insulation was compromised in some way already.

They missed an opportunity with this truck to get rid of all wiring completely. Make the giga-frame negative, and the exoskeleton positive.

800v of crowd control

Unfortunately I think that would make the exoskeleton the sacrificial anode, so even more likely to corrode.

That’s perfect. It can take out the owner when they bridge the two, and then self-disintegrate to leave no evidence of it’s existence in this world. Really a win-win.

That’s extra cost and weight that you can take up with stainless steel cladding!

…haha