The DMV is truly an engineer’s worst nightmare. Long inefficient lines, social interaction with your community, and a mandatory self portrait to top it off. The horror! But the bureaucratic machine does raise some interesting questions from time to time. If you’ve studied for a Commercial Drivers License (CDL) you may have come across a question that looks something like this: “When is an alcohol evaporator is especially important? A: In Cold Weather B: In Hot weather or C: In Dry weather.” If you answered A, you are either a trucker who started their career when Eisenhower was in office, or you’re just a good guesser. Alcohol Evaporators were once a pretty common upgrade to an air brake system, particularly for trucks that spent time in colder climates. To understand why they were once a choice upgrade requires some understanding of how an Air Brake system operates.

[Editor’s Note: Rob Peterson is a young engineer working in the trucking industry. He likes writing technical stories about old-school engineering tech like swamp coolers. If you’re also an enginerd who wants to write about car tech, email david@autopian.com. -DT] [image]

Let’s have a look at what an air brake system looks like on a big truck.

A Little Intro On Air Brakes Used On Trucks

Some important components of the system include:

- Air Compressor– Driven while engine is in operation and supplies pressurized air to the system

- Storage Reservoirs– Stores compressed air. Includes safety valve that bleeds air out around 150 psi as well as a drain valve for purging water/oil out of the system

- Treadle Valve (Brake Pedal/Valve) – What the driver uses to engage the system. Feels radically different from a hydraulic pedal — very little “give.”

- Air/Brake Chambers – There’s one chamber per wheel. It’s a mini reservoir to feed the brake cylinder (most trucks use an S-cam drum brake design). These are those bulbs you see under trucks (more on that later).

Air brakes are a totally different animal from hydraulic systems found in passenger vehicles. The obvious difference is that the fluid transferring braking pressure is air instead of liquid brake fluid. These systems hiss and squeal and pop and can make you spill your coffee if you’re dozing off. When starting the vehicle, a crucial pre trip check is watching air pressure build within the system via a dial gauge on the dash. As a safety mechanism, often there is a mechanical spring in the chambers to hold the truck in place if the pressure is low (this is the park brake, or “spring brake,” and is released via a hand control valve in the cabin). As for the service brake/foot brake, it sends pressure to the brake chambers to apply the brakes; it can be a little touchy with little to no pedal travel; some practice and finesse is key.

If you have replaced brake fluid in a car you are likely familiar with the tedious bleeding process. What you are doing is servicing a closed system in which the brake fluid is effectively isolated from the outside world. However air brake systems are open with the compressor sucking up air from outside the vehicle. As a result, moisture content in the air is able to enter the system. This is concerning because this moisture could condense when cold and form ice within brake lines. Jammed up lines could mean locked up wheels or brake shoes unable to actuate.

This problem can typically be solved by draining air reservoirs after drives, integrating an air dryer device, or by having a dedicated “wet tank” that collects water in the system. Additionally, the majority of trucks today are equipped with dual air brake systems. Each system controls half of the vehicle’s brakes as an additional safeguard against catastrophic failure. More in depth analysis of air brake components can be found in this article written by our ever-talented David Tracy. As a side note: David answers a key question, which is: Why are air brakes used? He explains that they are favored in heavy duty applications:

You may be wondering why this system is so different than what you’ve got in your car. Part of the reason, per a cursory Google search, has to do with the fact that traditional vehicle hydraulic brake systems are too vulnerable. A hole in a brake line or hose renders that entire brake system/subsystem useless. A hole in a pneumatic line or hose isn’t as big of a deal, since there are tanks right near each brake, and the tanks hold enough air for multiple brake applications.

David is referring to the air chambers/brake chambers mentioned prior that are sort of bulb-like in shape. Even if you found yourself with a leaking air line, that compressor will keep chugging away to try and replenish the reserves. Whereas, a hydraulic system would bleed itself dry after a few “come to Jesus” pumps of the brake pedal leaving you coasting into hopefully a big pile of pillows. More importantly, the park brake/spring brake will save you in the event of an issue with the pneumatic brakes. From David’s story:

The spring brake is the park brake; it’s called the spring brake because, unlike the service brake, the brake is actually actuated by a spring and not by positive air pressure. Pulling a knob like the one below actuates a valve and applies air pressure to the spring brake, releasing this brake. This means a leak in the air system — which would compromise your service brakes since those brake require air pressure to function — will actuate the park brake, making it act as an emergency brake. It’s a failsafe.

Even though the industry has moved on, if you’re interested in archaic, impractical, hazardous solutions to the whole moisture-in-brake-system problem, alcohol just may be the tool for you.

Using Alcohol To Prevent Brakes From Freezing

Here’s where the HillBilly magic kicks in. You likely already know that Vodka is best served fresh out of the freezer. Despite it being similar in appearance to water, the liquid remains.. well.. liquid when exposed to subzero temps. The freezing point of alcoholic beverages is largely dependent on their alcoholic concentration. Obviously, water’s freezing point is 0 degrees, but alcohol’s is lower than minus 150 degrees. Mix the two, and you’ll end up with a freezing point between those two figures.

If you are curious to see alcohol’s low freezing point in action, this science experiment with thoroughly underwhelmed children should suffice.

As I understand it, why alcohol has a lower freezing point than water largely has to do with the atomic properties of the substance. In case you are not aware, this world is made up of clusters of atoms. Solids have rigid structures of atoms vibrating, liquids are freer flowing streams of sticky atoms, and gasses consist of rambunctious atoms bouncing all over the place. The movement of atoms can be described their kinetic energy, which is directly related to temperature.

Whether or not the soup of atoms exists in a solid, liquid, or gaseous state is partly dependent on whether the atoms’ kinetic energy is strong enough to break intermolecular forces. Water forms strong hydrogen bonds between molecules which lends itself to freezing. In the case of H2O, there is not enough kinetic energy to break intermolecular forces at 32°F. Not enough kinetic energy means the bonds dominate and ice forms. However, the types of bonds alcohol molecules form with one another are not nearly as strong, which means kinetic energy overwhelms intermolecular forces until the temperature is brought to more extreme lows. The chances of encountering -173 °F on your delivery route are pretty slim unless Jeff Bezos starts a prime service for residents of Jupiter.

This property is the fundamental principle behind Alcohol Evaporators in air brake systems. Historically these devices are usually used in tandem with air dryers, as old designs were not as effective as ones used today. Moisture that bypassed the dryer could be diluted with alcohol downstream.

Air dryers are easy to spot on a truck. They are usually mounted somewhat near the air reservoirs after the compressor and are similar in appearance to an oil filter but flipped up like a Subaru’s and larger in scale. For a brief period of time during the mid 20th century these two devices coupled together were pretty standard procedure.

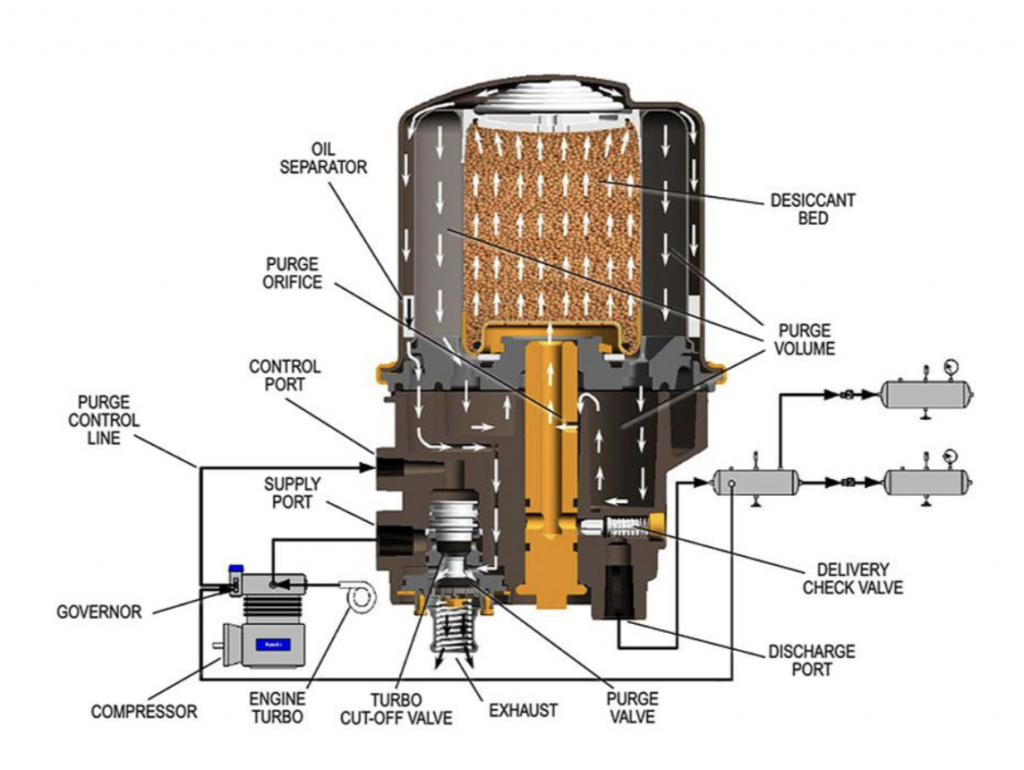

The air dryer itself is fairly fascinating, involving a special “desiccant” whose job it is to trap water from oncoming air. There’s also an oil separator. Check it out:

Trucksales.com gets into how a dryer works, writing:

The principle behind a desiccant dryer is to remove moisture and contaminants before the air reaches the first reservoir tank – commonly known as the ‘wet tank’.How they work involves a simple procedure; air travels through the end cover assembly – called the charge cycle – it’s direction in flow changes several times, reducing the temperature and causing contaminants to condense and drop in the bottom of the sump. After exiting the end cover, the air flows into the desiccant cartridge. Once in the desiccant cartridge, air first flows through an oil separator located between the inner and outer shells of the cartridge. The separator removes water in liquid form as well as oil and solid contaminants.Air, along with the remaining water vapour, is further cooled as it exits the oil separator and continues to flow upward between the outer and inner shells.Upon reaching the top of the cartridge, the air reverses direction of flow and enters the desiccant drying bed. The air is then drawn through a bed of clay beads.The special clay attracts water molecules which adhere to the beads’ surfaces. The moisture is “adsorbed” onto the beads’ surface rather than absorbed by soaking into the beads. Keeping moisture on the beads’ surface allows the moisture to be removed, greatly extending the life of the desiccant.

The article also mentions a purge cycle in the air brake system that involves opening a purge valve and using air to shoot contaminants out of the dryer. Plus, the writer notes that the desiccant has to be replaced every now and then.

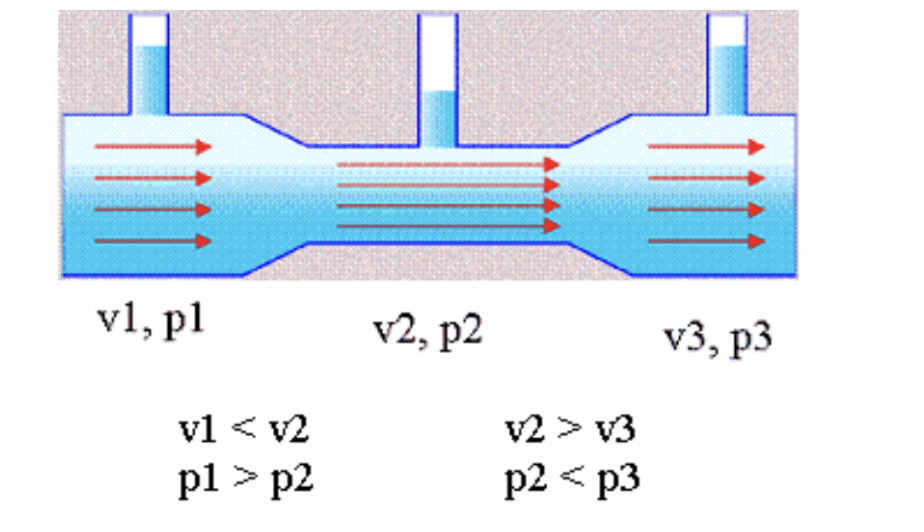

The alcohol evaporator is also mounted upstream from the air reservoirs. According to Haldex, compressed air rushes through a series of venturi passages and over the liquid reservoir of methyl alcohol. This interaction mixes alcohol into the air stream (methyl alcohol is hygroscopic (absorbs moisture) and miscible with water (i.e. they mix well)) before exiting through a check valve that prevents back flow.

Fluids that pass through a venturi experience a special effect. A venturi is a passage of varying diameter. You can picture it as if two nozzles were joined together at their small ends. While in the larger diameter part of the passage, the fluids are under higher pressure and experience a lower velocity. While in the section with a small diameter, the fluid trades pressure for velocity and it rushes through. This process is also critical to how a carburetor mixes air and vaporized gasoline before combustion. Air from a bowl (or in this case a chamber) is at ambient pressure; the low pressure at the venturi pulls the gasoline (or alcohol in this case) in.

Alcohol evaporators — which the maker of the evaporator shown above, Haldex, describes as “automatic vaporizing device[s] for keeping air lines and air reservoirs free of ice” — are not without their flaws. For one, alcohol has a corrosive nature especially when in contact with polymers and adhesives. Eating away at the air hose connections could result in a catastrophic leak on the vehicle, and that’s arguably worse than a bit of ice. There are a number of YouTube videos showing alcohol being poured directly into brake lines to get going in a pinch. However, I can’t advise repeating this procedure in good conscience. Alcohol is also a fairly volatile fluid which can ignite quickly. Jeff Celetano’s article Truck Air Brake System Maintenance on diesellaptops.com tells a cautionary tale about these devices:

“I was trying to retrieve a trailer using the yard horse, but the brakes were frozen solid. I crawled under with a torch and started heating up the air tanks and valves to thaw frozen brake valves. What I didn’t know was that the air tank was full of alcohol. Well, the tank exploded with such force it blew a hole through the floor of the trailer and bent floor bracing.”

Jeff reported suffering some hearing damage from the explosion but ultimately is lucky to still have a face. Stories like this are likely why the question remains on the CDL exam despite the devices long being out of vogue. Truckers often move from one vehicle to the next and have to quickly identify little differences in equipment and make a judgment call on the safety of the vehicle. However, if you find yourself operating a truck with one of these devices equipped, they can still be used with methanol-based airline antifreeze.

If there is any lesson to be learned from alcohol evaporators it’s that there are many ways to skin a cat. No… wait, leave Mittens alone. I mean, that in engineering there are often a number of solutions available to achieve a singular goal. Often these solutions are layered in a way that increases the factor of safety of a system. Each solution should be measured by its own merits as well as how it can pair with others. If one method fails, there should always be another ready to step in to get the job done. However, in the case of Alcohol Evaporators, I think the alcohol would be better suited for use in a cold drink after a strenuous day of wrenching.

We used high percentage isopropyl. One I remember was Truckahol. Yup, I’m old.

It depends on the pressure drop. But a complete drop to 0 psi equals max braking force, lock up all the tires.

Friendly neighborhood chemist here. Your description of freezing point depression is commonly used but isn’t quite right. The freezing point of the mixture is doesn’t have anything to do with the freezing points of the two substances that are mixed. For example, sodium chloride (table salt) has a boiling point of 1,465 Celsius (2,669 Fahrenheit), but if you mix it into water the freezing point of the solution will be reduced (and also the boiling point will be increased) compared to pure water. This has to do with the way in which the soluble substance is attracted to the water molecules, and this is why non-soluble substances don’t have this effect. Alcohol molecules, sodium ions and chloride ions are all attracted strongly to water molecules, so they interfere with the ability of the water molecules to “stick together” and form a solid. To allow the formation of a solid, you have to remove more energy from the system than you would for just pure water, causing the molecules to slow down enough that they have a chance to bond with each other and transition to the solid phase. There are also effects due to entropy, but they’re a lot harder to explain.

TLDR: Any substance that is soluble in water will reduce the freezing point and raise the boiling point compared to pure water, when it is dissolved to form a solution.

Thank you for the education as well as TLDR answer. The extent/specifics of intermolecular forces were a bit outside of my range of expertise but I did my best. Raises the question of why alcohol was ever chosen over less volatile fluids in the first place if there are other soluble fluids that would have the same effect.

-Rob

Kind of addressed in the article–Alcohol is hygroscopic so just having some *somewhere* in the system will actively remove any humidity that’s in the entire system, which helps prevent any problematic condensation. And though alcohol can be a bit corrosive/solvent-y, it’s really not that bad at all compared to most things that will readily dissolve in water (Contrast to, i.e., salt or acetone). It’s also very cheap and safe to handle.

Thank you for saying that so I don’t have to. Have you ever seen the addition of hexafluorobenzene to benzene? All of a sudden, you get pi stacking and the freezing point actually goes up.

“Obviously, water’s freezing point is 0 degrees, but alcohol’s is lower than minus 150 degrees.” This is the USA. We don’t do that centigrade stuff here.

We should, though.

In the old days, the alcohol reservoir was a glass jar. I think a Ball jar would mate with the Bendix-Westinghouse mount.

Another question: Why did the trucking industry take so long to move to disk brakes?

they are much more complex (and expensive) than the s-cam drums. A disc for a big truck weigs around 100 lbs. the calipers are about the same.

edit to add: discs are still a relative rarity on heavy trucks. the overwhelming majority still use drums.

also, interestingly, it takes a longer distance to stop an unloaded truck and trailer than a loaded one. The suspensions are designed to carry heavy weight and when they are unloaded, they are highly unstable. When you lock up the brakes, an empty trailer will hop and bounce whereas a loaded one will keep the tires planted and stop quicker.

See also friction and the normal force.

Another major factor that applies even beyond disc brakes. The industry is resistant to change and largely adheres to what is proven, reliable, and available. With the drum brakes, you knew you could get a replacement S-cam at any shop. Any road service would be able to get you back up and rolling. And often times, fixes were as simple as patching an airline, adding alcohol, or hitting it with a hammer. Newer technology, be it brakes, abs, collision avoidance, add new complexity that often times (right, wrong, or indifferent) does not bring enough value in they eyes of the carrier or driver.

True. Trucking is expensive and profits are thin, even in the best of times. When rates tank and fuel prices are high, many trucking outfits are forced to shut down. And now, on top of that, even basic parts are getting harder and harder to fine. Not many small outfits can withstand being shut down 30 days plus because the little electronic doohicky that your truck won’t run without, is on national backorder.

“You may be wondering why this system is so different than what you’ve got in your car. Part of the reason, per a cursory Google search, has to do with the fact that traditional vehicle hydraulic brake systems are too vulnerable. A hole in a brake line or hose renders that entire brake system/subsystem useless. A hole in a pneumatic line or hose isn’t as big of a deal, since there are tanks right near each brake, and the tanks hold enough air for multiple brake applications.”

I hate hydraulic brakes. The fluid is corrosive to paint, it is usually hydroscopic, and they are very vulnerable to damage, etc.

For me Pushrod brakes > Cable Brakes > Air Brakes > Hydraulic brakes.

So I guess you’re daily driving a model T? Hydraulic fluid for brakes is a compromise that is not ideal. The glycol ethers and borate esters have good thermal properties and low flammability but are hygroscopic and water contamination will lead to corrosion. They are also excellent paint solvents. Silicone oil (DOT 5) is better in those regards BUT cannot be used with ABS as it will foam.

Please write an article all about pushrod brakes and have David post it on the Autopian, I would love to learn more deceleration information.

It’s great to learn about different options and technologies for a similar application. I’m so tired of bleeding hands from my handbrake.

So if their brakes fail, do they call AAA? Or AA?

there is a website called TruckDown. You enter location and it gives a list of repair shops, mobile repair services, tire shops, and tow services within a specified radius. You start calling the phone numbers, go with whoever can get there quickest, and hope they dont take you to the cleaners on the bill.

You cage the spring brake with the failed line, pinch that line closed with a pair of vice grips and drive on.

What I’m about to write varies by carrier and climate: A best practice is to open the primary and secondary tank daily to purge water huffed by the air compressor. For example, at ski resorts it’s common to “blow the tanks” at the end of a shift in hopes any condensed water will be evacuated with the air.

Some fleets install automatic bleeders to accomplish this task. They’re great until they get stuck in the open position, which is common because the valves are underneath the vehicle where dirt, snow and other detritus showers the bleeders constantly. Source: Me. I once drove buses at a ski resort.

That would be an interesting job. I guess it would be common to be driving on slippery roads? Presumably you’d also sometimes need to make judgement calls on whether to continue?

(i have no experience with cold climates)

Yeah, you can drink the methanol. I’ll stick to good ol’ ethanol (and keep my vision). 😀

All alcohols are drinkable. Some are only drinkable once.

Sorry Mr. Pratchett, had to be done.

Some people are blind to the side-effects of drinking methanol.

Not specifically mentioned (unless I missed it) is something of which the layman will not be aware:

Hydraulic brakes – leak in the system, unable to stop.

Air brakes – leak in the system, you better get out of the way of traffic before it drops anchor because it’s fail safe (the air keeps the brakes from engaging) and like it or not, you’re stopping.

Went ahead and chucked in another quote from my old article. Thank you for the feedback!

Ive always wondered how abrupt that stop is. I guess they choose a compromise between locking up on slippery roads versus stopping ASAP ?

Well that’s the thing. It’s your choice how to handle this. You can, right away, like RIGHT NOW, come to a controlled stop as safely as possible and as out of the way as possible (and I’m pretty sure that’s why the alarm is so loud and annoying) or let it run out and yes it’s immediate slamming of the brakes, full stop NOW. So if you’re on an icy mountain pass might be time to get religion.

The air brake test is the one part where you can’t make any mistakes, at least in Virginia. Pretty sure other states too (they’re all different which is weird)

It all depends on where the leak is and how bad it is. For a leak that is before the treadle small leaks and the only indication is that when the truck is parked for a longer period the pressure is low when you return to the truck. Many consider it acceptable for it to leak to zero when parked for 8-12 hours. for a larger leak that results in the air in the tanks to drop below 90-100 psi the warning light and buzzer will go off while the spring brakes won’t start engaging until 50-60 psi.

Now a catastrophic failure that results in an immediate large drop in pressure, can cause them to come on quick and hard, sometimes just the brake that line services.

Yeah, honestly I never had it happen to me, but I felt it prudent to plan for the worst possible scenario.

Anecdotally, the systems I worked with would set off the loudest buzzer known to man at 75 PSI of air pressure remaining, the ride height starts sagging around 45 psi and the brakes are dragging at ~15 psi. I’m sure its possible to be real severe but in most instances it’s a slow process before you’re stuck.

Ok, I’ve got a trucking question that I’ve wondered about for years. With a log truck, when unloaded they carry the rear wheels up on the frame rails behind the cab. How the hell does it get up there? I’ve always assumed that whatever equipment is unloading the logs lifts it up there, but is there some other wizardry afoot?

That style utilizes a crane onboard to both load/unload the logs and “collapse” the unladen trailer.

Self-loaders have their specific setup, but it’s actually standard procedure for non-self-loader unloaded log trucks to carry the trailer up there, too.

Are there versions where the truck has a winch to do it? I ask because i’ve seen many of these trucks without cranes.

I *should* know this as i’ve lived near logging areas several times.File it under ‘not important enough to ask’ i guess

Most don’t have the self-loader setup, and they use trailer loaders at mills and other unloading points. Basically a large frame with a winch that pulls the trailer up so you can back the truck up and lower the trailer on.

There are a couple ways, actually, but they always involve additional equipment. There is basically a loop to hook on the trailer, and a loader can hook it (and usually will to get it down), but what often happens at the mill (or wherever else) is that the truck pulls through a trailer loader, which is a large metal frame holding a large winch. Lower the hook to the loop on the trailer, hook it up, and run it up. Then you back up and lower the trailer in.

I’ve been around them all my life and still find them kind of cool. It’s a pretty elegant solution to the problem.

There are self-loaders, so I guess I should not say you ALWAYS need outside equipment. But, at least in my neck of the woods, they are not used nearly as much. They have the equipment built on to load the logs, so they can also load the (specially designed for their setup) trailer.

Also important, but slightly unrelated to the question of how: log trucks pretty much invariably have some sort of protection for the back of the cab (don’t want a log getting through) that also serves as a rest/guide for the tongue of the trailer when it is loaded onto the truck.

Sorry for bombarding, but there is one more interesting detail about trailer loaders: they utilize an open hook. That allows for you to lower the trailer onto the truck, lower slightly more, and release the hook. Then you just run it back up. No need to climb up and unhook.

Thank you so much. I thought it was going to get some grief for asking a silly question. Just one of those random things you wonder about on the highway LOL. I see myself going down a rabbit hole on YouTube tonight…

Not a silly question; I only know because I grew up in logging country with a truck-driving father. If he didn’t own/operate a log truck, even being in logging country might not have been enough for me to know the details.

I’m embarrassed to say this but my dad drove log trucks when I was young before switching to Long haul. Unfortunately he passed before this question ever occurred to me. But my mom’s side of the family still runs a small logging outfit… I really am embarrassed to have not known all that but I appreciate the education!

It looks like you got half of the answer, I could be wrong. The ‘rear wheels up on the frame’ is likely a ‘lift’ or ‘tag’ axle. These are special axles that raise and lower depending on the load the truck is carrying. They usually pivot on a large bracket mounted on the frame that’s controlled by a separate air bag. With the wheels up, you save a good bit of fuel economy with the trade-off being more complexity. Pretty neat stuff. Thanks for reading!

-Rob

I didn’t read the question as referencing the tag axle, but the trailer. Perhaps that is just because I know a lot of log truckers who don’t have a tag axle. Thanks for the additional info, though, since the tag axle is a pretty common mystery for non-truck people. “Why aren’t those wheels on the ground all the time?” or “Are those spare tires up there?” are typical questions.

I think an article about tag axles would also be a good read, if you aren’t already planning on it!

The log truckers I know call it a drop axle, but that might be a PNW- or logging-specific term.

I have heard the term drop axle as well. Not super familiar with logging applications so I’ll take your word for it with the crane and trailer. I’m sure there’s a bunch of neat modifications and devices specific to that industry worth looking into. Thanks for the help!

I’m excited to read more from you, because most of the trucking knowledge I have is very specific to logging, which I know is VERY different from long-haul or other freight. And I don’t have even half the knowledge of my dad, who is an owner/operator and therefore does a lot of his own repairs and maintenance. He showed me some things, but he also urged me not to go into logging or trucking, so there was a lot he didn’t show/tell.

Excited to learn more!

I’ve hear the term for all types of trucks in the PNW and it can refer to one placed anywhere on the truck. I’ve also heard the term lift axle to refer to them in any location. You also hear the term pusher for one located in front of the drive wheels and tag for those located behind the drive wheels, though that can also refer to a non-adjustable axle. The other thing that you will see usually on concrete and dump trucks is a trailing or stinger axle. https://www.superdumps.com/trailing_axles/ again to comply with Bridge Formula regs when loaded and retractable for dumping and unloaded driving.

On-site many will lift those axles in low traction situations to increase the weight on the drive axles.

As mentioned in many cases the trailer is unloaded at the harvest site with the same equipment used to put the logs on the truck and at the mill they may use the same equipment to unload or a dedicated device to get the loader to the next truck quicker. Other trucks do have self loaders that load the logs onto the truck as well as the trailer on to the truck. The other wizardry is that trucks that the draw bar is collapsable so that it fits within the trucks length when stored and extends for use. Very similar to what is used on Pup style dump trailers, in those they are extended to comply with bridge formula laws and to dump the truck w/o unhooking the trailer. The collapse them for maneuvering in tight spaces and when running empty.